If you’re traveling on Yosemite Valley’s Northside Drive, you might notice a two-story wooden structure just south of the road, across from the Valley Visitor Center and Yosemite Museum. The U-shaped building’s sharply angled cedar-shingled roof, granite chimneys and log pilasters call to mind high peaks rising out of a forest.

The Rangers’ Club in Yosemite Valley is a hallmark of the “rustic style” that prevailed in park architecture for decades. Photo: Courtesy of NPS.

A small sign at the building’s entrance. (Photo courtesy of the Yosemite Nature Notes “Rangers’ Club” episode.)

As you approach the building, you’ll see a sign noting its name: Rangers’ Club.

And if you were to step inside, you’d find a central, spacious lounge and library, with reading nooks, tables and a large granite fireplace. The two first-floor wings hold a kitchen, pantry and bedrooms; more bedrooms line the second floor.

This month marks 100 years since the dedication of the Yosemite Rangers’ Club. If you dig into the story, you’ll find that the club isn’t just a century-old building tucked in a shady patch of Yosemite Valley. From its granite foundation to its pointed roof, the structure is steeped in the history of park rangers, park architecture and park philanthropy — and, especially, of Stephen Mather.

Stephen Tyng Mather was born in San Francisco in 1867, graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1887, and then headed east to work as a reporter in New York. After a few years in journalism, he followed his father into the borax industry, a lucrative move that eventually made him a millionaire.

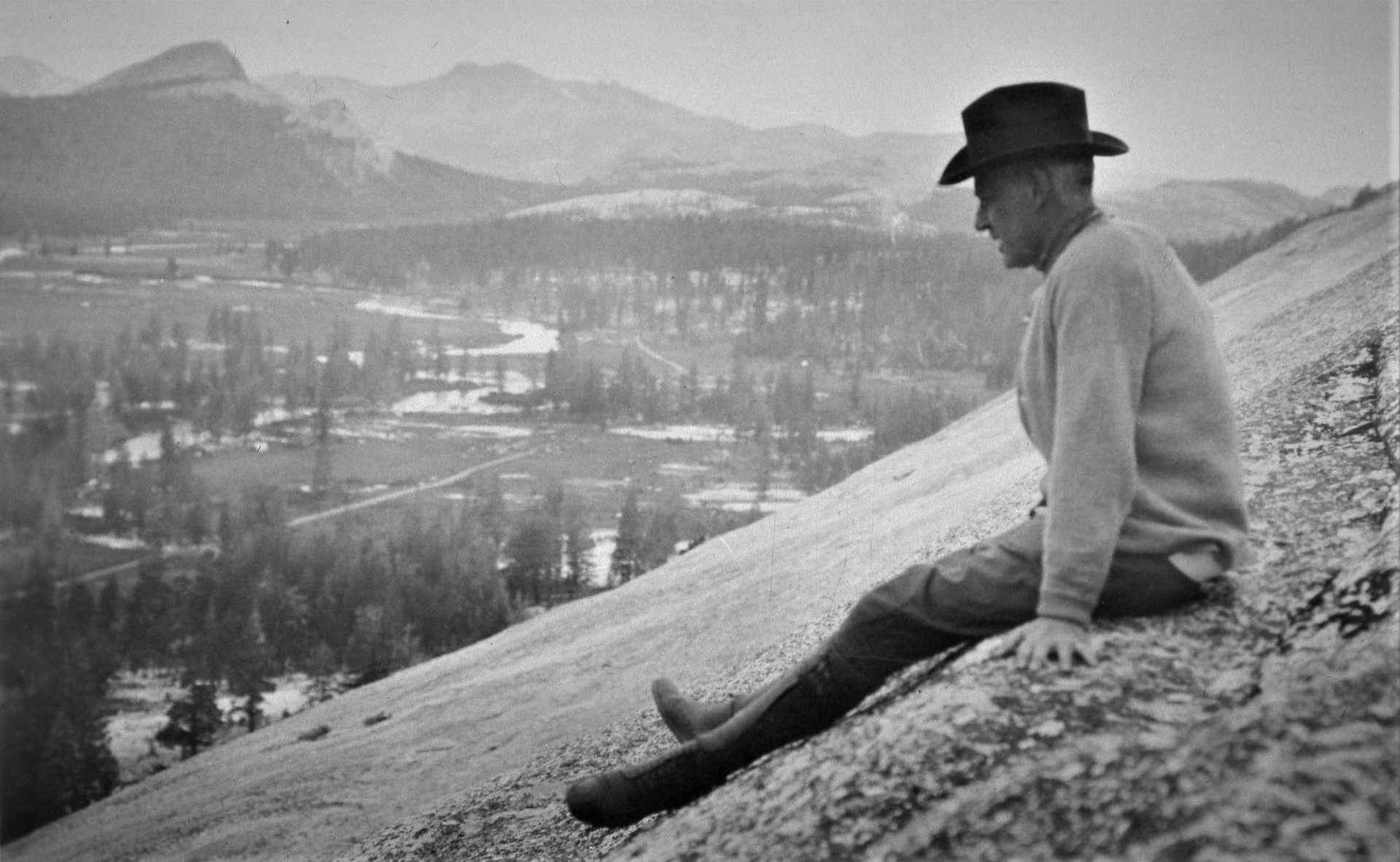

Stephen Mather on Lembert Dome in Tuolumne Meadows, in 1921. Photo: NPS/Francis P. Farquhar (Yosemite Historic Photo Collection).

Mather, a longtime nature lover, lobbied for the creation of the National Park Service, which was established in 1916. He became the bureau’s first director. At the time, the NPS oversaw about two dozen national parks and monuments. To Mather, Yosemite stood out.

“There is no question that Yosemite was his favorite of all the parks, and he spent time there every year,” Mather’s assistant Horace Albright later recalled. “It was the place where he launched his newest programs, tried out his ideas, and worked to enlarge and improve the concessions.”

In 1915, in an early act of park-focused philanthropy, Mather raised and donated funds to purchase the Tioga Road so it could be transferred from private to federal ownership.

As NPS director, Mather turned his love for Yosemite toward a dream for the park’s budding workforce and developed areas. In the early 1900s, civilian rangers had replaced the soldiers that had been dispatched to serve in Yosemite and other parks. By 1919, Yosemite had 21 civilian rangers, tasked with educating tourists, protecting wildlife and enforcing laws, and housed in a medley of cabins, tents, old military structures and studios.

Mather saw housing as a core element of developing and retaining a professional workforce, and the Rangers’ Club was essential to that vision.

In dreaming up new quarters for Yosemite’s rangers, Mather drew on a May 1918 letter from Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane, which offered the following architectural instructions for national parks:

In the construction of roads, trails, buildings, and other improvements, particular attention must be devoted always to the harmonizing of these improvements with the landscape. This is a most important item in our program of development and requires the employment of trained engineers who either possess a knowledge of landscape architecture or have a proper appreciation of the esthetic value of park lands.

(Lane’s letter also included guidance on outdoor recreation, education, stock grazing, logging, concessions, and factors to consider when expanding the new “national playground system.”)

The Rangers’ Club coming together, piece by piece. Photo: NPS (Yosemite Historic Photo Collection).

A photo of Mather above a plaque honoring his role in creating the Rangers’ Club. Photo: NPS, 1926 (Yosemite Historic Photo Collection).

The plans for the club meshed with a broader scheme to design a cohesive “village” on the north side of the Valley, replacing the ad hoc collection of buildings that had sprung up on the south side of the Merced River.

Charles Punchard, the NPS landscape engineer, collaborated with architect Charles Sumner on the design for the Rangers’ Club. They worked within the then fledgling, now famous NPS “rustic style,” which dictated that buildings should reflect and blend in with their surroundings, incorporate natural materials and evoke the local landscape.

Rustic style prevailed across the NPS for decades, and is visible in nearby Yosemite Village buildings, such as the museum and post office, which were both built in the 1920s. The Rangers’ Club was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, and later designated a National Historic Landmark, in part because of the central role it played in developing and demonstrating rustic style.

Costs for designing and building the club far exceeded the federal appropriations limit for park construction, which at the time was $1,500. As the price tag soared, Mather made a sizable personal donation to help pay for the building; the final cost surpassed $30,000. Construction began in April 1920, and the building was dedicated five months later, on September 26, in a ceremony attended by park leaders, businessmen and, of course, Mather.

After the dedication, park rangers finished painting and staining, installed lights, and then settled into their new home. Mather regularly stayed in the club on visits to the park.

Four years after the building was dedicated, a plaque was hung on a stone wall inside the club, with the inscription: “This tablet has been placed by the officers and rangers of Yosemite National Park, as a mark of their appreciation of Stephen T. Mather, Director of the National Park Service, for his personal gift of this building, the Officers and Rangers Club House, which has already contributed so much to their comfort. November the 16th, 1924.”

The Rangers’ Club became the physical representation of Mather’s devotion to not only Yosemite, but also to the National Park Service.

– from the Rangers’ Club Historic Structure Report (2011)

Though originally envisioned as the first of many such living spaces for national park rangers, the Yosemite Rangers’ Club remained unique in the National Park System.

The club has evolved over the years. Crews have installed new heating systems, fire escapes and stairs; repaired the deck, railings and roof; upgraded the kitchen; rebuilt the foundation; made the building more accessible to people with physical disabilities; conducted a seismic retrofit; and more.

This historic photo of the Rangers’ Club living room and fireplace are featured in the Yosemite Nature Notes “Rangers’ Club” episode.

The 100-year-old Rangers’ Club fireplace before (left) and partway through restoration work (right) in summer 2020. Photo: NPS.

This year, with support from our donors, a historic preservation crew is restoring the stone fireplace that has for a century served as a focal point and gathering place in the club’s main lounge. By restoring the mortar and repairing the firebox — and by reinstalling the original fireplace tool holder, which turned up in the club’s attic a few years ago — they’re ensuring the safety and stability of the feature while preserving its historic masonry and character.

A hundred years after it was built, the Rangers’ Club is still standing, still housing rangers, and still serving as a tangible symbol of early park philanthropy and park architecture, and of Mather’s vision for a professional corps of park rangers.

What will the next 100 years bring for Yosemite and other parks? Who will wear the rangers’ flat hats over the next century? What will park philanthropy prioritize and accomplish? We can’t predict what the future holds for public lands, but one thing is certain: The generosity of people who love, support and steward the parks will continue to play an essential role in places such as Yosemite.

Watch the “Yosemite Nature Notes” episode on the Rangers’ Club, from 2011, for an inside look at the history and significance of the building:

Learn more about the Rangers’ Club on the Yosemite National Park website and in the 2011 Rangers’ Club Historic Structure Report.

* Horace Albright, in “The Birth of the National Park Service: The Founding Years, 1913-1933,” and also quoted in the Rangers’ Club Historic Structure Report.