Depending on where you go in Yosemite, there’s a good chance you’ll encounter some wildlife: deer and coyotes in the Valley, marmots sunning on high country rocks, black bears searching for acorns in the woods.

Here’s one animal you’re not likely to come across: a Sierra Nevada red fox. These rare, elusive mammals, a California state-threatened species, live high up in the Sierra and Cascade mountains, where they roam remote forests and subsist on small prey and manzanita berries.

For nearly a century, no one saw the rare fox within park boundaries. Then, at the end of 2014, a remote camera captured an image of one trotting through the snow in the northern Yosemite Wilderness — the first confirmed sighting of the species in the park since 1916.

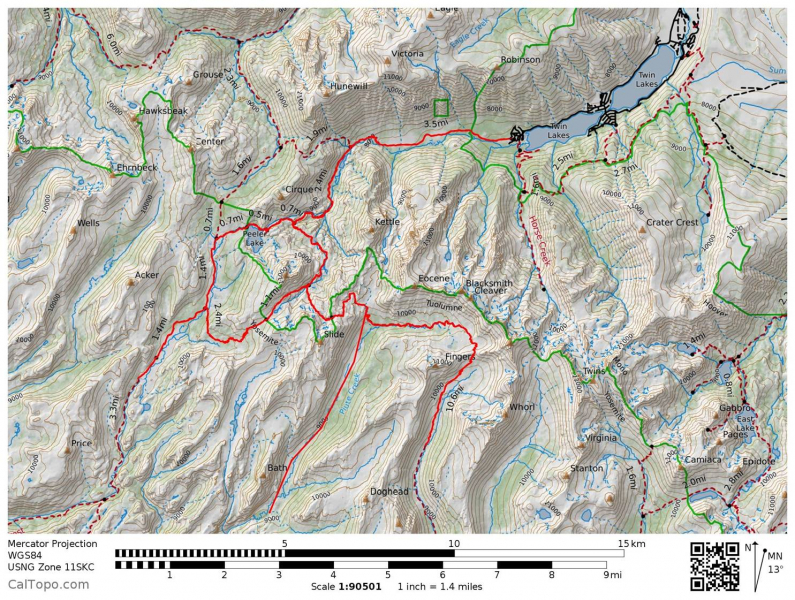

After that initial headline-making image, researchers continued searching for signs of the species. With support from Conservancy donors, they installed motion-activated cameras covering dozens of hexagonal study cells in northwestern Yosemite, a honeycomb of scientific possibilities spanning vast untrammeled terrain.

As of June 2017, researchers had pored over thousands of motion-triggered images and confirmed eight fox sightings: one in 2014, two in 2015, three in 2016, and two in 2017. Along the way, they also gathered information about competitor and prey species that share the fox’s remote habitat.

Our project coordinator, Ryan, has gotten an inside look at the work behind those precious snapshots (and behind another fox research technique: scat surveys). In October 2015, he joined a research crew for a three-day expedition to set up new camera survey stations. Sixteen months later, in the midst of a record-breaking winter that saw 41 feet of snow pile up in the high country, he headed out with the crew once again — this time, on skis. Read on for a look at his experience skiing for science in Yosemite!

Over the course of a week, the crew covered 51 miles, skiing up passes and down canyons to locate and place camera stations. They put their ski skins and stamina to the test, climbing as much as 3,900 feet in a single day.

Day one! Ryan and the rest of the crew struck out from the Twin Lakes trailhead on February 24, under a bright blue afternoon sky. Heavy packs held everything the crew would need for the multiday trip: food, dry clothes, camping gear, and, of course, scientific equipment.

A stern reminder of nature’s volatility appeared as they made their way into the wilderness: the remnants of an avalanche. All the crew members had completed avalanche training before the trip, and had to pay close attention to warning signs of slides as they navigated the snowy terrain.

After getting caught in driving wind and snow on their first night, the crew awoke to calmer conditions on day two. Refreshed by solid sleep, a good breakfast and plenty of water, they set off to find a camera station they hadn’t been able to locate the evening before. By 8:15 am, they had shoveled out the base of their target tree and unearthed (er, unsnowed) the camera and hair snare. Off to a good start!

And on to the next site! The crew assessed conditions and decided it was safe to make the tough trek up and over Mule Pass. From the high point (elevation 10,489 feet), they took in the view of Sawtooth Ridge, Matterhorn Peak and the Finger Peaks before cruising down the fresh, untouched snow.

Teamwork is an essential element of any group wilderness trip … and certainly comes in handy when your trip involves lots of shoveling, careful note-taking and regularly handling sensitive camera gear.

On the way down Mule Pass, Ryan and the crew stopped to refresh another survey station before continuing their journey, leaving the camera to capture images of whatever life might cross its path in the wilderness for another few weeks.

On day three, the crew left the shelter of their base camp below Mule Pass and split into pairs – two set off to check and move five cameras in Matterhorn Canyon, the other two went to investigate another series of survey stations in Piute Canyon. This photo captures the calm before another storm: Ryan and crewmate Mike had already made it to four of their five cameras, but still had plenty of ground to cover before returning to camp. Soon, snow started to fall.

The storm continued overnight, and the crew awoke on day four to almost a foot of fresh snow on their tents. Conditions weren’t much better inside Ryan and Mike’s tent – the lightweight, single-wall structure was easy to carry, but limited ventilation meant a constant battle against condensation accumulating and freezing on the interior.Their “storm kitchen tent” (a black tarp anchored over a deep shoveled-out hollow) offered ample air flow, and allowed them to melt snow and cook meals despite the continuous precipitation. Glamorous? No. Functional? Sure.

By day five, the skies had cleared enough for a team photo op at the top of Mule Pass, with Sawtooth Ridge providing a dramatic backdrop. Pictured (left to right): Brian, Mike and Toren. Not pictured (behind the camera): Ryan.

Some of Ryan’s photos might make fieldwork look like an extra adventurous ski vacation, but throughout the week, the crew was focused on their primary goal: making sure the red fox research could continue as seamlessly as possible. Sometimes, that meant stripping off warm gloves to remove memory cards and record important data.

The survey protocol called for each camera to capture images for a minimum of 20 consecutive days. The crew had to figure out whether the cameras had met that minimum, and then reset or move them for another round of data collection. First, they had to find the survey stations, which were often buried far beneath the snow.

In this shot from day six, Mike positions a new camera. Each device had to be aimed north – otherwise, the path of the sun might trigger the motion-activated camera and drain the batteries.

Working in the wilderness can mean frozen toes, damp tents and sore muscles … but it also means opportunities to experiences moments like this, watching the mountains glow at last light miles from any other humans.

Day seven dawned sunny and clear – perfect conditions for drying out gear before packing up one last time. Here’s how Ryan describes their final morning: There is a certain excitement that comes on the exit day as you anticipate the return to walking on solid earth after seven days of skiing and camping on snow. I took my coffee and sat in the sun to enjoy the still winter morning one last time. Somehow the frozen toes mattered less on that last day, and the joy of being in the Yosemite Wilderness during the epic winter of 2017 was overwhelming.

With a mile to go before returning to Twin Lakes, Ryan stopped for one last look at Crown Peak. Work accomplished, he and the crew skied back to solid ground, leaving behind the remote saddles and forests that provide crucial habitat for the Sierra Nevada red fox. Behind them, ski tracks in the snowfields served as a subtle, fleeting reminder of another step in efforts to deepen scientific understanding of one of North America’s rarest mammals.

That weeklong expedition contributed to the 252 visits that Yosemite’s carnivore crews made to set, check or remove cameras during the 2016-17 season, a notable achievement made possible by donors’ support. They collected approximately 23,000 motion-activated images showing at least 14 species, including snowshoe hares, American martens, bobcats, porcupines and Clark’s nutcrackers. Sifting through those images also revealed a precious finding: at least three new detections of the Sierra Nevada red fox.

Every brief glimpse of a Sierra Nevada red fox, and of the animals that share its remote habitat, can remind us of the importance of keeping protected landscapes pristine and wild. The next time you heed the mountains’ call, remember the often unseen creatures that rely on the forests, meadows and rivers along your path, and the simple steps you can take to minimize your impact. And in the meantime, enjoy this final glimpse of science in the snow:

Photos and video by Ryan Kelly, February 2017

1 thought on “Skiing for Science”

Comments are closed.