This story about the hundred year history of Yosemite Conservancy appeared in our spring/summer magazine 2023, and was written by Peter Bartelme.

Museum cornerstone being laid and New Village dedication. Stephen Mather on the right in the center.

On a frigid fall day nearly a century ago, a group of people dressed in their Sunday finery stood under Yosemite Valley’s towering black oaks to celebrate the construction of the Yosemite Museum.

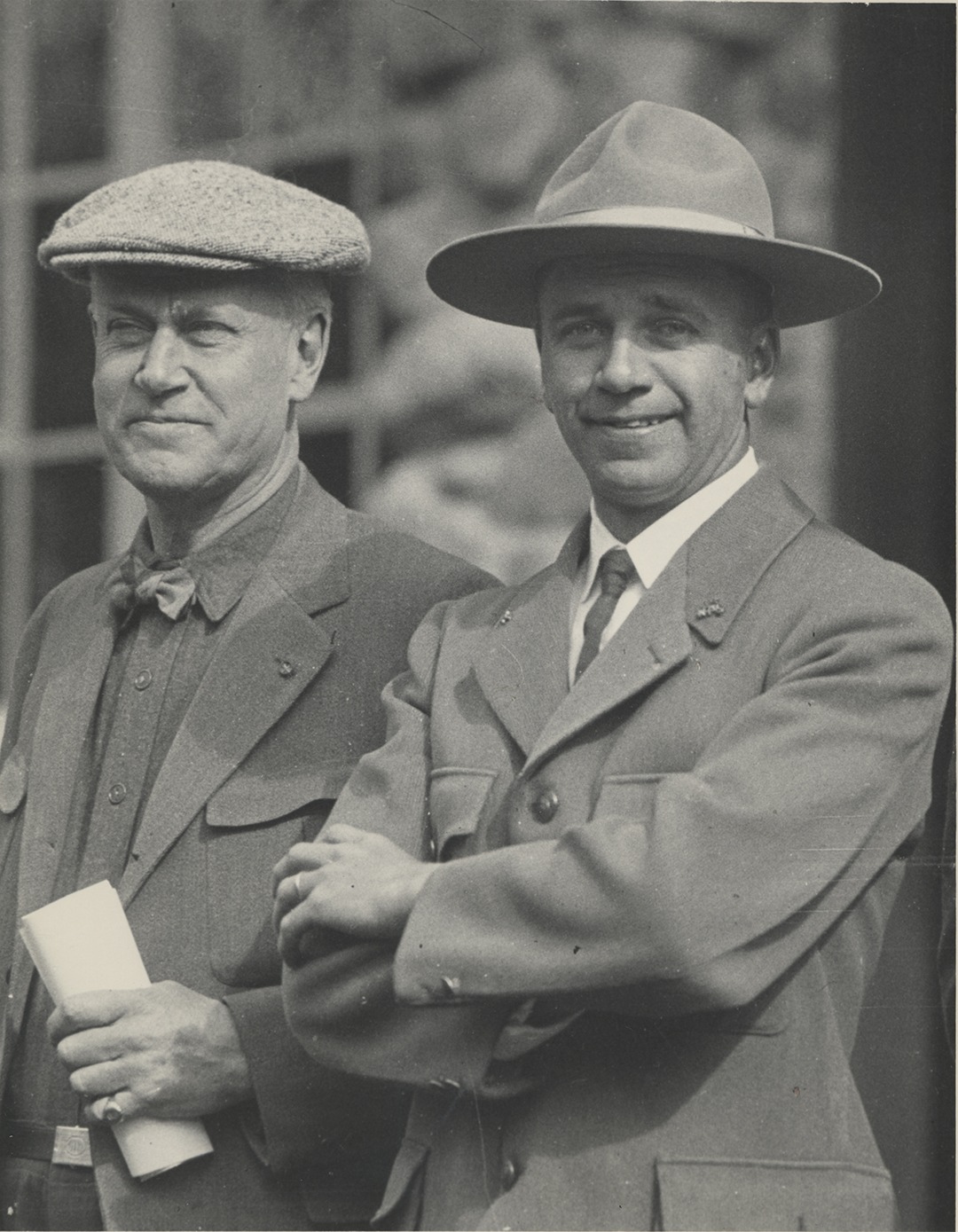

Among them were Stephen Mather, the National Park Service’s first director, and Ansel Hall, the first chief naturalist. As the crowd cheered, the two conservation pioneers stood beside a granite boulder that was about to be hoisted into place as the building’s cornerstone — a moment that symbolized the launch of a movement.

Stephen Mather dressed in street clothes standing along side of park ranger Ansel Hall dressed in uniform at the Yosemite Post Office. Image: NPS

This pivotal point was years in the making. Hall had toured museums and other far-flung places to gather ideas for the museum’s design. Funding was secured from the Rockefeller family, specifically from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial, which John D. Rockefeller had launched in 1918 in honor of his deceased wife. A year before the ceremony, in 1923, Hall had created a special bank account under the name “Yosemite Museum Association,” effectively creating the National Park Service’s first nonprofit partner.

During the next 100 years, the group’s name would change as its mission and accomplishments grew: Yosemite Museum Association; Yosemite Natural History Association; Yosemite Association; Yosemite Fund, a fundraising offshoot; and finally, today’s Yosemite Conservancy. Threaded through these decades has been a continuing dedication to the park and its protectors — with partnerships as the cornerstone of its success.

“That brisk morning changed the way people thought about how to more effectively steward public lands with private funds,” says Frank Dean, Yosemite Conservancy president. “The concept of partner organizations supporting our national parks took root in Yosemite.”

What began in Yosemite under those black oaks soon spread. Supporters created the Grand Canyon Association in 1932, the Yellowstone Association in 1933, and Southwest Monuments in 1938. These and more than 200 other nonprofit groups have contributed hundreds of millions of dollars to national parks — donating more than $400 million in 2022 alone to National Park Service projects and programs across the country.

Yosemite’s nonprofit partner was the catalyst. Working with the National Park Service, the organization offered interpretive programs, trained naturalists, launched art and theater projects, and published books and the Yosemite Nature Notes periodical.

It also helped launch fundraising programs for notable projects, such as the reintroduction of bighorn sheep around Tioga Pass. And in 1988, the group’s “Return to Light” fundraising campaign spawned the Yosemite Fund, a separate organization created to raise money for major park projects.

One early donor to the fund was Dave Dornsife, chairman of Herrick Corporation, a steel manufacturer. He and his wife, Dana, contributed funds and supplied the steel for bear-proof food lockers, a key part of the park’s successful effort to wean bears from human food.

“After several encounters with bears stealing my food on backcountry hikes, I wanted to fix the problem. “We teamed up with the National Park Service and created a design that worked so well that we have donated hundreds of boxes,” Dornsife says. “Over 30 years, Dana and I are proud to have donated the steel to provide tangible benefits to major projects like the bridges for trails at Tenaya Lake, Yosemite Falls, Mariposa Grove, and Bridalveil Fall.”

Sequoia seedlings growing in Mariposa Grove.

In 2010, the Yosemite Fund and Yosemite Association united to create today’s Yosemite Conservancy.

“The work supported by partner organizations had a snowball effect,” Dean says. “The prototype for bear-proof food lockers in Yosemite became the template for other parks. Wildlife managers from different parks share information to protect species, such as Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep, monarch butterflies, and Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs. That was made possible with the advent of partner organizations and dedicated donors.”

During the past century in Yosemite, generous donors have contributed over $152 million for more than 800 completed projects. This includes restoration of trails and habitat, wildlife protection, and education programs. Donors’ impacts can be seen at renovated overlooks, such as Tunnel View, Olmsted Point, and Glacier Point; the Lower Yosemite Fall Trail; Happy Isles Nature Center; the renovation of Parsons Memorial Lodge; the restored Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias; and more.

Park-loving donors range from philanthropists to children giving their birthday money. One teen hiked the John Muir Trail as a fundraiser. A sixth-grade teacher donates annually and brings her class to the park to energize the next generation of conservationists. The Pitzer Family Foundation gave $1 million this year for improvements to the Mist Trail, which snakes up the Merced River to Vernal Fall and is one of the most popular trails in the entire National Park System.

An adult peregrine falcon in flight (July 2017). Peregrines in Yosemite are now thriving thanks to Yosemite Conservancy donor supported wildlife management. Image: James McGrew

And then there’s Mary Watt, the longest-running monthly donor, contributing every month for 37 years, who began volunteering for the organization in 1986. A self-proclaimed “nature girl” drawn to Yosemite’s natural history, Watt looks to the Conservancy’s efforts to save peregrine falcons for inspiration.

“When only two pairs of peregrine falcons existed in California, I thought I’d never see one in the wild,” she says. “They’re flourishing today in Yosemite and elsewhere. It’s proof that when there’s enough people that care, we can bring back something from the brink, make great change, and light a spark in humans to do remarkable things.”

Mary Watt’s spirit of giving. The power of partnerships. A better park. Moments such as these during the past 100 years capture all this potential, much like the cheering crowd under the tall oaks watching a crew move a granite cornerstone into place.