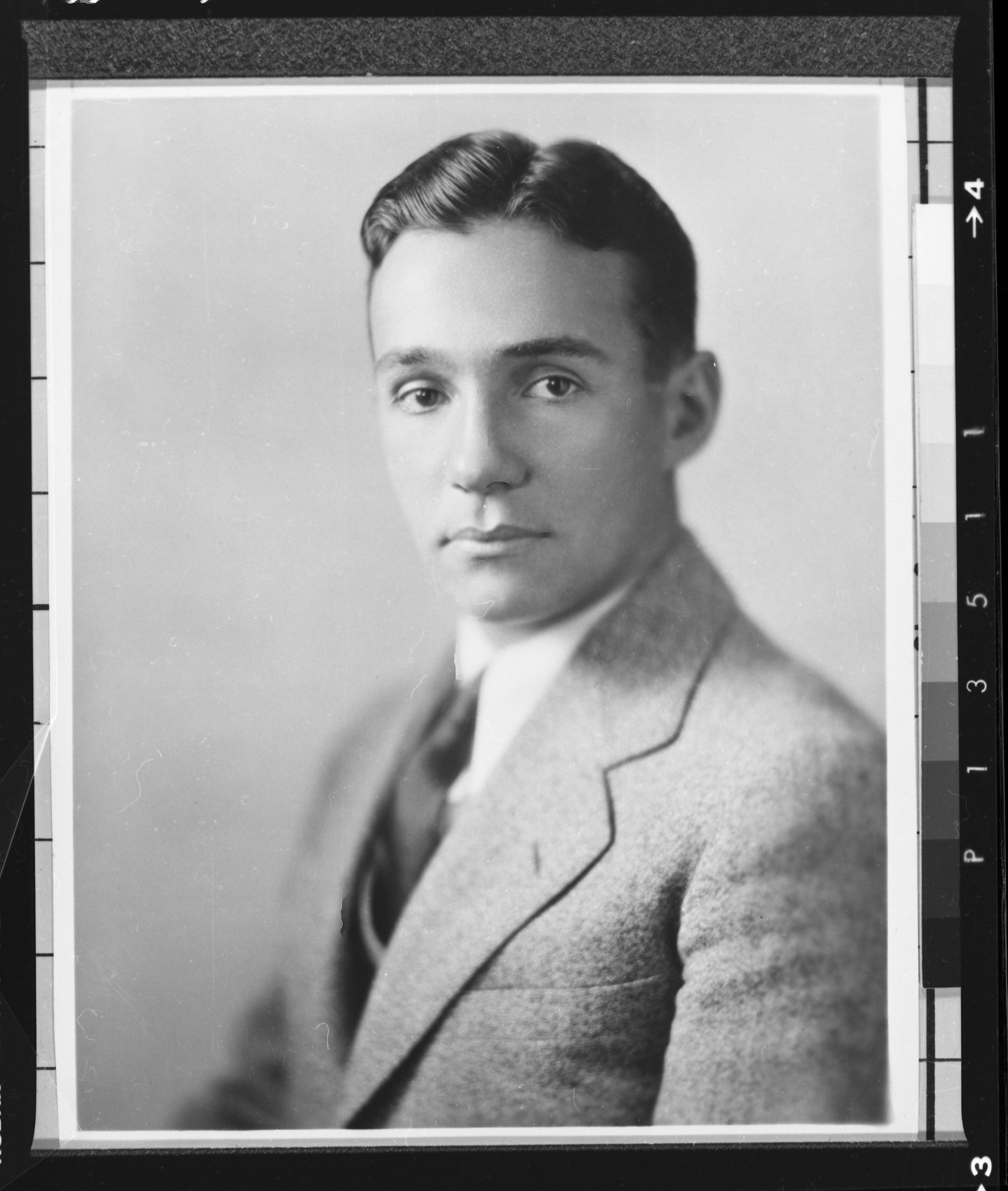

Portrait of George Meléndez Wright, courtesy of NPS. George Melendez Wright was instrumental in shifting National Park Service attitudes toward wildlife. While rangers hunted mountain lions and other predators in Yosemite, and put out hay to feed elk and bison in Yellowstone, he lobbied to permit natural systems to function intact and with minimal interference.

A nature and wildlife enthusiast from an early age, San Francisco native George Meléndez Wright often explored Yosemite’s backcountry while in college at University of California, Berkeley.

Wright became an assistant park naturalist in Yosemite National Park in 1927. It was the beginning of a career that would profoundly affect wildlife and natural resource management throughout the United States. He wrote articles for Yosemite Nature Notes, was a teacher of field classes in the park, and helped develop the Yosemite Museum.

During his first years working in the park, Wright grew concerned about the negative impact of humans on wildlife. With no staff devoted to the issue, he volunteered to conduct a survey of wildlife and plant conditions in the national parks using money he had inherited from his father. Spending more than half of his inheritance, Wright funded the entire project himself for three years, until the National Park Service (NPS) finally designated a wildlife budget.

While conducting his surveys, Wright witnessed terrible treatment and killing of wildlife in parks across the country. He documented everything he saw, soon calling for a change in natural resource management policies, as well as a formal wildlife division at NPS.

When NPS Director Horace Albright established the Wildlife Division of NPS in 1933, he named Wright as its first chief. Wright led the division to prominence, and in 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him to head the National Resources Board. Wright spent the next two years traveling to and researching areas where new national parks could be established.

Sadly, Wright was killed in a 1936 car accident at age 31. But his contributions to institutional reform in NPS and to wildlife conservation and resource management nationwide still live every day in the parks he loved so much. There are mountains named for him in Denali National Park & Preserve and Big Bend National Park.

The following story appeared in the Fall 2009 issue of Yosemite Journal, the predecessor to the Yosemite Conservancy Magazine.

A Personal Tribute

By Pamela Meléndez Wright Lloyd

On February 25, 1936, at the age of 31, my father, George Meléndez Wright, was killed in an auto accident. I was only two and a half years old, too young to remember him. But over the years I came to know him through the personal remembrances of my mother, Bee Wright Shuman, other family members, friends and colleagues, the legacy of his work and his professional writing.

My father was a pioneering and visionary biologist in the early days of natural resource conservation and the National Park Service. Long before concepts such as “ecosystem,” “environmentally sound,” and “sustainability” had been coined, George Wright’s ecological perspective and philosophy pointed to the need for science-based management of the national parks.

Even today, 70 years later, my father’s life, work and writing are greatly respected and continue to influence the Park Service and beyond. George Wright articulated a philosophy, indeed a vision, which not only transcends his life and times but speaks to us across the years with stunning clarity and relevance.

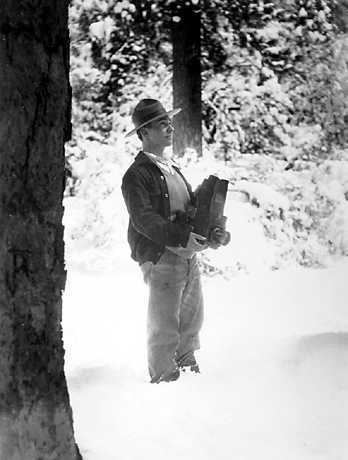

Wright with camera in Yosemite National Park, ca 1928. Image courtesy of Wright family.

My father’s national stature and historical importance should not obscure his origins and strong California ties. His roots were grounded in the San Francisco Bay Area where he was born, raised and educated. He attended San Francisco’s Lowell High School, where he was president of the Audubon Club and senior class president, and went on to the University of California, Berkeley, where he studied forestry and vertebrate zoology. From his teens on, Wright was hiking and exploring the backcountry of the West Coast. These trips fueled his interest in wildlife research and honed his skills as a field biologist and naturalist.

My father found “his” park—Yosemite—long before he came to work there. He would return there again and again for the rest of his life. Working as assistant naturalist between 1927 and 1929, he put his own imprint on Yosemite National Park by helping to develop the museum in the Valley, teaching field classes, conducting field studies of fauna and flora, and writing many articles for Yosemite Nature Notes, this publication’s predecessor.

My father’s deep and abiding attachment to Yosemite and the Sierra became part of his legacy to his family. Long before the 1970s and the modern environmental movement, I grasped the importance of what my father believed in and stood for: his love of wilderness and wildlife; his sure knowledge of the need to tread lightly on the natural world; and especially his first love, birds.

Succeeding generations of our family—George Wright’s children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren—have followed in his footsteps along mountain paths, feeling a special affinity for Yosemite and the Sierra, the places that gave him such great joy and inspiration for his life’s work.

A California native and Marin County resident, Pamela Meléndez Wright Lloyd has long been involved with government and community organizations committed to environmental education, preservation, protection and stewardship. She and her husband Jim visit Yosemite every chance they get.