A version of this story appeared in Yosemite Conservancy’s November 2020 magazine.

Curiosity is often at the core of uncovering history. For Yosemite ranger Yenyen Chan, curiosity about Chinese history in the park has led to a decades-long journey of unearthing and sharing stories that might otherwise have gone untold.

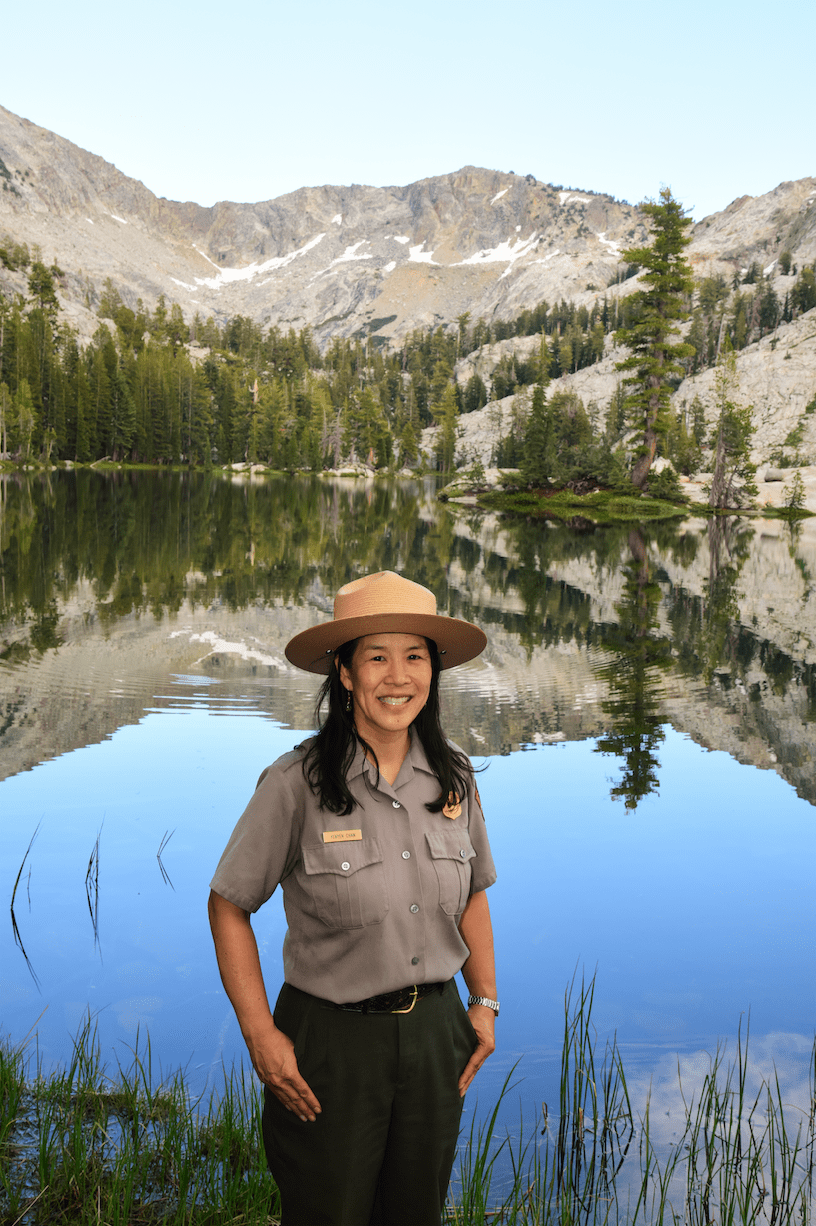

Yosemite ranger Yenyen Chan, pictured here near Sing Peak, has spent years researching and sharing Chinese history in the park. Photo: Christine White Loberg.

Roads to the past

Chan’s enthusiasm for studying Chinese history in Yosemite was sparked in 1993, when she was working as a park intern in Tuolumne Meadows and was surprised to learn that Chinese workers had played a central role in building the famous Tioga Road.

Many years later, after returning to work as a park ranger, Chan was asked to lead a Yosemite Association program focused on the history of Chinese workers in the park. She agreed, and jumped into research.

Chan learned that Chinese immigrants began to move to the West Coast in the 1840s, often seeking opportunities in the gold rush to support their families in China, where social and environmental disasters were ravaging many regions. California’s Foreign Miners’ Tax of 1850 forced Chinese immigrants to search for work beyond gold mining, including in agriculture and railroad construction.

In Yosemite, Chinese immigrants made up most of the workforce that built the Wawona Road — during just 18 weeks, in winter, using only handpicks and shovels. And, as Chan had learned in 1993, Chinese laborers helped build the 56-mile Great Sierra Wagon Road, today’s Tioga Road, in the 1880s. The crew worked in rugged terrain on foot, without machinery, using dangerous blasting powder to clear the route and hand tools to build retaining walls. According to one report, 250 Chinese and 90 European-American laborers completed the road in just 130 days.

The history of Chinese road workers lives on in the Conservancy-supported Washburn Trail, too, which stretches for two miles from the Mariposa Grove Welcome Plaza up to the famous giant sequoias. The trail was built over the course of two years and opened to the public in late 2018. Part of the trail follows the footprint of the old Washburn Road, which featured stone walls built by Chinese masons and once carried stagecoach travelers between Wawona and Mariposa Grove.

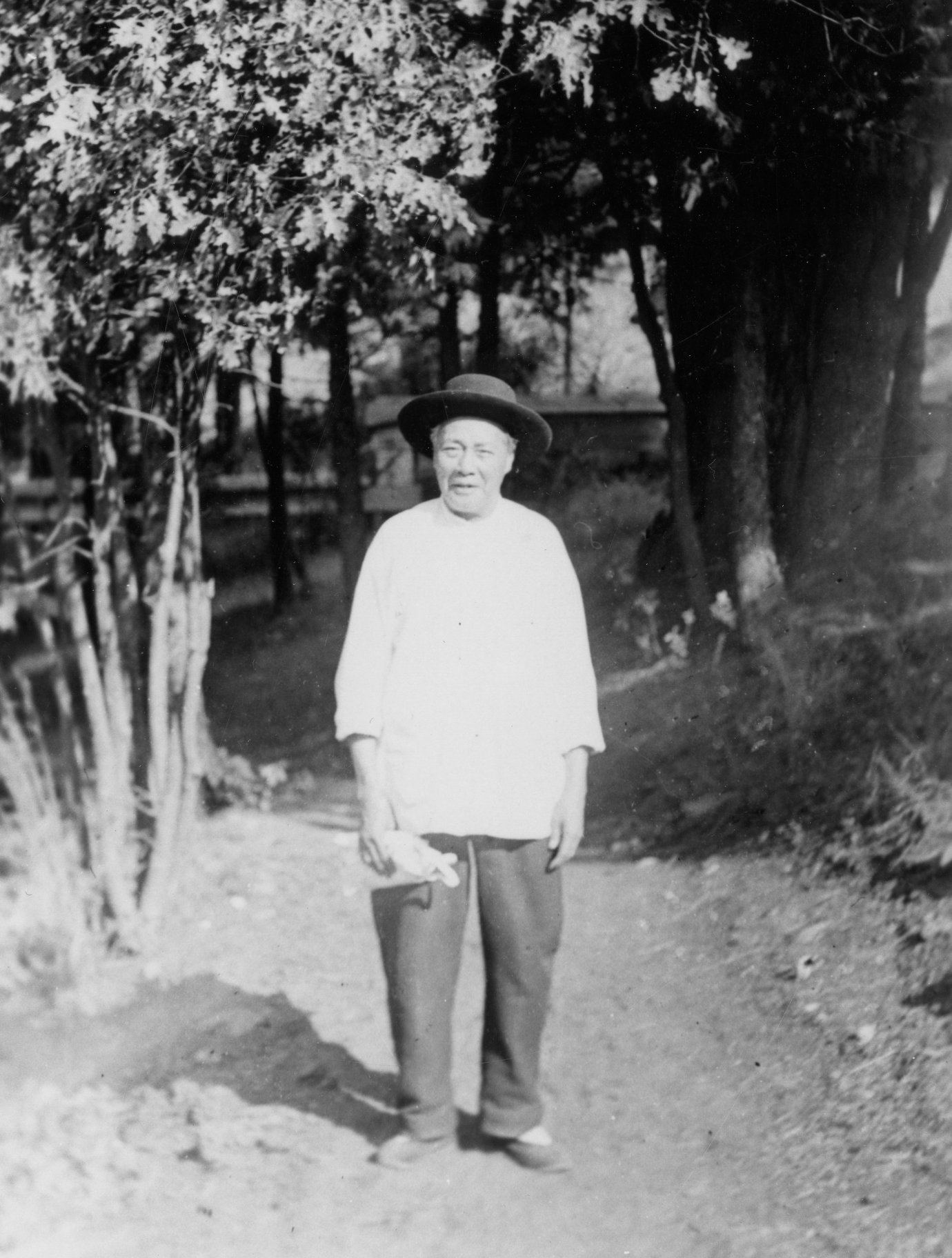

Ah Louie worked as head chef at the Wawona Hotel in the early 1900s. Photo: Yosemite Archives.

Culinary tales

Chan’s research led her into the stories of Chinese chefs who worked in and around the park, including Ah You, who was born in China in 1848 and arrived in California at age 21. The Washburn family hired Ah You as head chef at their Wawona Hotel in 1886. He stayed on in the kitchen when Ah Louie took over the head chef role in 1910, and both men continued cooking for the hotel until the property changed hands in the early 1930s.

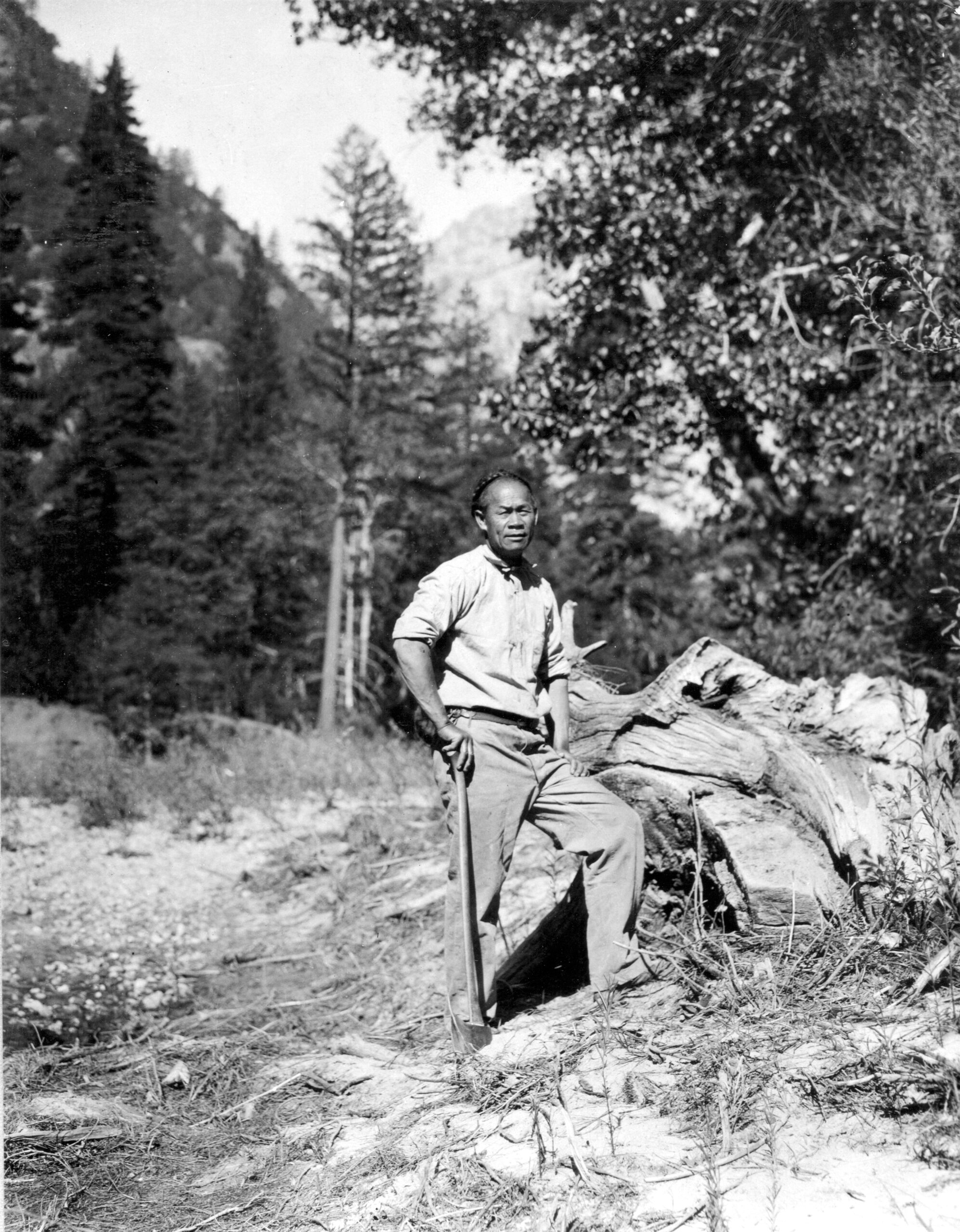

Another celebrated Chinese chef, Tie Sing, had been working for the U.S. Geological Survey for nearly three decades when Robert Marshall, the USGS chief geographer, tapped him to cater Stephen Mather’s July 1915 “Mountain Party.” Mather, who was then serving as special assistant to the secretary of the interior, had brought together a group of men from the worlds of government, publishing, engineering, business and conservation for a two-week trek through Sequoia National Park, with the goal of solidifying support for the creation of a dedicated federal agency to oversee the national parks.

Famed backcountry chef Tie Sing. Photo: U.S. Geological Survey.

In “Creating the National Park Service: The Missing Years,” Horace Albright, who had served as Mather’s assistant, recapped his experience with the “party” in an account amply seasoned with descriptions of Sing’s culinary creations. From Sing’s mobile field kitchen, Albright recalled, the group feasted on breakfasts of “fresh fruit, cereal, steak, potatoes, hot cakes and maple syrup, sausage, eggs, hot rolls and coffee,” on packed lunches, and on hearty dinners that covered a sweeping menu of items, such as soups and salads, trout, fried chicken, venison, and pie.

Mules carried silverware, pots and pans, linens, and ingredients from camp to camp. Albright recounts inventive strategies for transporting and preserving food on the trail: Sing and his assistant, Eugene, wrapped meat in damp newspaper to keep it cool, and kept fresh bread dough close to mules’ bodies, letting it rise throughout the day before baking it in the evening. (By Albright’s account, the daily bread continued until a mule stumbled off a cliff; the animal climbed back up relatively unscathed, but the sourdough starter it had been carrying was lost.)

One evening, when the group descended Mt. Whitney in a storm, Sing “surpassed his previous wonders” by dishing up plum pudding. The group’s final meal was “superb — more than usually superb,” Albright wrote, and ended with special pastries that held personalized “future fortunes” written by Sing.

Hiking into history

As Albright notes, Sing’s renown as a backcountry chef was well-established long before that feast-filled 1915 trek; 16 years earlier, a mountain in the southern Sierra Nevada had been named in his honor. Today, Sing Peak, on Yosemite’s southern boundary, is the destination of a backpacking trip that ranger Chan helps lead as part of an annual event focused on the park’s Chinese history.

Ranger Yenyen Chan talks to a group of participants in Yosemite Valley during the annual Yosemite-Sing Peak Pilgrimage event in 2019. Photo: Courtesy of NPS.

The “Chinese laundry” building in Wawona, before (above) and after restoration. Photos: Courtesy of NPS.

A few years ago, participants in that annual Yosemite-Sing Peak Pilgrimage stopped by a small wooden structure in Wawona. Through her research, Chan had learned that the building had once housed a laundry run by Chinese workers, and later became a carriage shop. Over the years, however, the building had fallen into disrepair, and much of its history was lost with it.

Restoring a building — and a story

When Conservancy donors Sandra and Franklin Yee learned about our 2019 grant to the National Park Service to restore the laundry building and its connections to Chinese history, they were so inspired that they decided to significantly increase their support by making a generous major gift to fully fund the work.

Park preservation experts repaired windows, eaves and siding; rebuilt the front porch; and removed modern plumbing and electrical utilities, with the goal of returning the building to its original state. The project also included developing new educational exhibits about Chinese history in the park.

Yosemite Conservancy donors Sandra and Franklin Yee outside the cabin in Wawona that has been in Sandra’s family since the 1950s. Photo: Sabrina Diaz.

For the Yees, funding the laundry restoration was an opportunity to honor Chinese American history, the immigrant story and their own family’s deep personal connections to Yosemite. Sandra’s parents, Hogan and Ruth Wong, bought a cabin in Wawona in 1953, and her family has visited the park every summer since 1949. Today, Yosemite remains a touchstone for the Yees’ children and grandchildren, and it is a place to honor their ancestors.

Thanks to Chan and the Yees’ curiosity and passion, stories of Chinese history in Yosemite are coming to light, in Wawona and beyond.

Above: Ranger Yenyen Chan on Lembert Dome, in Tuolumne Meadows (photo courtesy of Yenyen Chan).