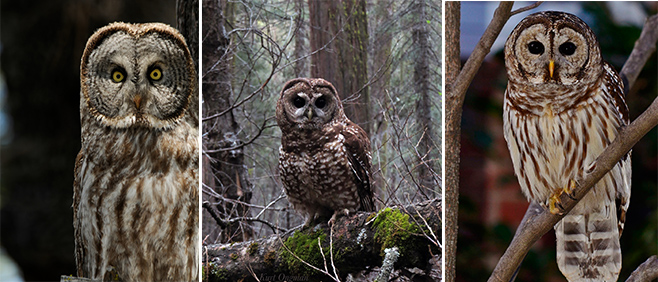

Can you spot the spotted owl?

Hint: It’s the one with the spots. See it? The middle one. That’s the California spotted owl (Strix occidentalis occidentalis), a large, brown bird with dark facial disks, dark eyes and, as the name suggests, white spots on its body. Its neighbor to the left, the great gray owl (Strix nebulosi), is far larger, with a gray body and yellow eyes; the one to the right, the barred owl (Strix varia), has streaks instead of the tell-tale dots.

We’ll get back to the barred owl, but for now, let’s focus on our spotted subject. Spotted owls live in forests with large, old trees, finding homes in broken tree-tops, in trunk cavities or in abandoned nests. They hunt in the dark, gliding silently through forests to snatch flying squirrels, woodrats, bats and other small animals from the ground — or in mid-air. And when they do make noise, they can produce more than a dozen different calls, though primarily use a series of four hoots. (Take a listen to this spotted owl recording from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library.)

The spotted owls in Yosemite represent one of three subspecies of Strix occidentalis. Northern spotted owls (Strix occidentalis caurina) are dark brown with small white spots, and live in the northwestern U.S. and British Columbia; Mexican spotted owls (Strix occidentalis lucida) are the lightest of the three, with large white spots, and live in the southwestern U.S. and Mexico; and California spotted owls (Strix occidentalis occidentalis) fall in the middle, both in looks and geography: medium brown, medium white spots, with a habitat limited to its namesake state.

Habitat loss affects all three subspecies. Two have spent more than 20 years listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, receiving that designation in 1990 (northern) and 1993 (Mexican). The third, the California spotted owl, remains federally unlisted after multiple petitions in recent years (2000, 2004, 2014 and 2015); its listing is currently under review, and it has been designated a California Bird Species of Special Concern.

As described in the California Department of Fish and Wildlife species account, Strix occidentalis occidentalis, like the other two subspecies, faces challenges from logging, development, wildfires and other factors jeopardizing its forest habitat. Spotted owls can serve as indicators for the broader health of mature forests throughout California; likewise, understanding how shifts in the landscape affect the owls can inform efforts to manage and protect the species and their natural domain.

In 2016, our donors are funding a second year of spotted owl-focused studies in Yosemite, part of a larger research effort that also examines the park’s genetically distinct subspecies of great gray owls (Strix nebulosa Yosemitensis). Working in the wake of the 2013 Rim Fire, scientists are learning how wildfires have affected the owl populations that depend on Yosemite’s mature mixed-conifer forests.

In 2016, our donors are funding a second year of spotted owl-focused studies in Yosemite, part of a larger research effort that also examines the park’s genetically distinct subspecies of great gray owls (Strix nebulosa Yosemitensis). Working in the wake of the 2013 Rim Fire, scientists are learning how wildfires have affected the owl populations that depend on Yosemite’s mature mixed-conifer forests.

This year, the park’s six-person owl field crew is looking for spotted owl nests in burned and unburned areas. Approximately half of known spotted owl nesting sites are within or adjacent to the footprint of the Rim Fire, which burned more than 78,000 acres in Yosemite. Initial results from previous donor-funded research show that many of the owls have returned to their nesting areas, but it’s unclear whether they are breeding successfully.

The crew kicked off the research season a few months into the year, heading into boulder-strewn forests to hunt for pellets and feathers, watch for the flash of widespread wings, and tiptoe through meadows and tree stands, mimicking owl calls and listening for an unmistakable four-note reply.

In the midst of those patient hours of surveying, some of the scientists took time to share their expertise with participants in two of our Outdoor Adventure programs, giving visitors a firsthand look at owl research. By the end of spring, the crew had discovered a new spotted owl nest tree and detected individuals at 24 of 35 survey sites.

Amid those patiently, carefully executed surveys, a new factor emerged: A barred owl (Strix varia — remember the photo at the start of this story?) was sighted in Yosemite for the first time. Native to eastern North America, barred owls began shifting west in the early 20th century, and were first reported in the Sierra Nevada in 1991. They share a genus and habitat requirements with spotted owls, making them competitors.

Barred owls have the advantage: They are larger and more aggressive than their spotted relatives, and feed on a wider variety of prey. Research has shown that spotted owl populations decline in areas where they overlap with barred owls.

While park scientists work with other agencies to address this important observation on a regional level, they’re continuing the fire-focused studies and getting ready to dig deeper into the data collected over the past few years. As they survey for signs of adult and juvenile spotted owls, they’re collecting information that will help them determine how fire affects the birds’ breeding success. Is fire always a destructive force for the species? Or are there conditions under which fire can preserve, or even create, owl habitat?

While park scientists work with other agencies to address this important observation on a regional level, they’re continuing the fire-focused studies and getting ready to dig deeper into the data collected over the past few years. As they survey for signs of adult and juvenile spotted owls, they’re collecting information that will help them determine how fire affects the birds’ breeding success. Is fire always a destructive force for the species? Or are there conditions under which fire can preserve, or even create, owl habitat?

Results from their research will shape plans for managing forests, fires and other resources, and will inform future petitions for federal listing. With your support, this work is expanding our understanding of Yosemite’s spotted owls, the threats they face in a changing Sierra landscape, and the best ways to protect this elegant, elusive bird for generations to come.