From the ground, El Capitan looks smooth, its gleaming granite polished by long-ago glaciers. As you get closer, though, cracks and crevices take shape. A dark figure appears at a ledge. You catch a glimpse of white chest, a sharp beak and yellow eyes, and then …

Lift-off! The peregrine falcon launches, gliding on a 40-inch wingspan over Yosemite Valley, before transforming into an avian arrow, skydiving in a “stoop” that can surpass 200 miles per hour. After striking its prey, the peregrine returns to the wall, where nestlings wait for their meal.

An adult peregrine falcon glides through the air while hunting in Yosemite Valley. Photo: James McGrew.

Avian wanderers

Peregrine falcons, whose name fittingly means “wanderer,” are found on six continents and always nest high above the ground. In urban areas, they make homes on tall structures; in the wild, they look for cliffs, such as the ones lining Yosemite Valley.

Adult peregrines have a dark gray back, black head and white chest, with sharp yellow beaks. Young peregrines, called juveniles, are fluffier, with streaked coloring and a brown face mask.

Peregrines prey on other birds, and on bats; they often catch their meals in mid-air. They dwell at the top of the food chain, though this does not protect them from other threats, including those driven by human activity.

An adult peregrine and two fluffy chicks peer out from a rocky nest site. Photo: Julie Miller.

Population plummet

Before the mid-20th century, there were more than 3,800 adult peregrine pairs in the United States. That number started to plummet in the 1950s; by 1974, only 324 pairs remained, with zero in Yosemite.

The culprit: dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT), a pesticide. Insects ingested DDT; small birds ingested insects; and falcons ingested small birds, swallowing a concentrated toxin that made eggshells so dangerously fragile that adult peregrines would accidentally crush their eggs.

Peregrines were declared a federally endangered species in 1970, and they were added to the California endangered species list the following year. In 1972, DDT was banned in the U.S.

A juvenile peregrine falcon eyes the sky. Just out of view: an adult falcon soaring overhead. Photo: James McGrew.

Back from the brink

Thanks to a nationwide ban on DDT and concerted rehabilitation efforts, peregrines have made a comeback. A 2006 survey estimated that populations in the U.S. had rebounded to at least 3,000 pairs. The falcons were removed from the federal endangered species list in 1999, and from the California list in 2009 (though they remain a “fully protected” species in the state).

While Yosemite’s walls and domes offer ideal habitat for the recovering raptor, they remain vulnerable to human disturbance. That rocky habitat also makes the park a coveted climbing destination. Seeing peregrines up close can be awe-inspiring for a climber; for the falcons, that interaction is potentially fatal. Young falcons depend on their parents for food and protection; if climbers accidentally scare adult falcons from the walls, the nestlings might starve or be eaten.

Park managers, however, see climbers not as a threat to Yosemite’s peregrine population, but as part of the long-term solution to protecting them. In the early years of recovery efforts, Yosemite climbers worked with wildlife experts to replace DDT-thinned eggs with healthy chicks in cliffside falcon nests. Since then, thanks to an innovative peregrine-protection program supported by our donors, climbers have continued to play a key role in ensuring the park’s fast-flying falcons continue to thrive.

A Yosemite wildlife researcher uses a telescope to zoom in on peregrine territory during a seasonal survey. Photo: NPS/Liz Bartholomew.

Saving Yosemite’s peregrines

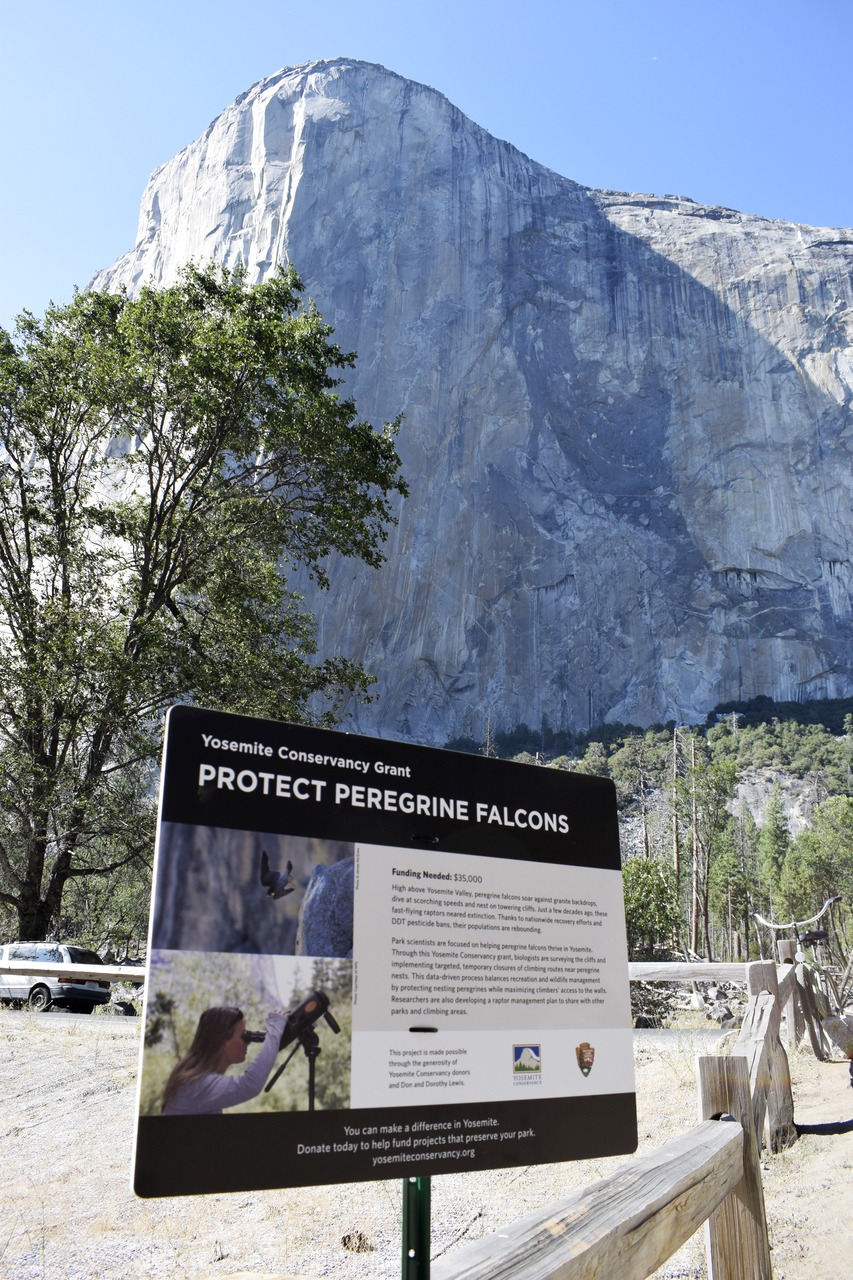

Yosemite Conservancy donors help fund the park’s well-established, proven approach to protecting peregrine falcons. Photo: Yosemite Conservancy/Ryan Kelly.

In the early 1990s, Conservancy donors helped fund efforts to restore the park’s falcon population. In 2009, biologist Jeff Maurer launched a program to protect peregrines through targeted closures of climbing areas; after his death that same year, his family made a gift in his memory to ensure his work could go on.

Between 2009 and 2019, Yosemite researchers observed 21 peregrine pair territories and 31 new eyrie sites, more than double the numbers documented between 1978 and 2008; they also detected 251 young falcons that reached fledgling stage.

Yosemite’s successful strategy stands out for its focus on balancing falcon management and visitor recreation. Rather than issuing indiscriminate climbing closures, Yosemite researchers and rangers implement data-driven, responsive regulations. Wildlife managers survey dozens of cliff sites to search for and monitor nests throughout the season, and they impose, adjust or lift closures based on each peregrine family’s activity.

The first closures are typically implemented in mid-March. Over the next few months, researchers observe nesting activity and adjust closures accordingly. Their observations also inform decisions about creating buffer zones above the cliffs to prevent helicopters from flying unnecessarily close to falcon nests.

At the height of the closure period, under 5 percent of climbing routes are closed; all routes are usually back open by mid-July, once young peregrines have left their nests.

A collaborative effort

Temporary signs near climbing areas alert hikers and climbers when routes are closed to protect peregrine nesting sites. Photo: Yosemite Conservancy/Keith Walklet.

The Yosemite climbing community plays a crucial role in ensuring the success of the park’s proactive, adaptive approach to protecting peregrines. Climbers learn about which routes are temporarily off-limits, and about the importance of respecting the closures, via signs posted near climbing routes, through updates on the Yosemite National Park website, at “climber coffee” gatherings, and during conversations with climbing rangers (and with one another). Their partnership is an essential element of the process: By avoiding off-limits areas and educating fellow adventurers, climbers help ensure falcon fledglings have the best chance of survival.

Today, our donors’ support continues to help the park protect peregrines. In 2019, the peregrine team studied 27 cliff sites, from iconic Valley features such as El Capitan and Glacier Point to locations in the high country and Wawona, and documented 14 falcon pairs. They also completed a survey protocol guide for future falcon fieldwork, and they plan to develop resources for other parks and agencies that manage areas where climbers and peregrines overlap.

For decades, climbers and wildlife managers have worked together in Yosemite to help peregrines thrive on the walls. Thanks to their ongoing efforts — and our donors’ support — you might catch a glimpse of a remarkable success story in action on a future Yosemite visit: a falcon saved from extinction, floating and diving in the Sierra sky.

A peregrine falcon glides high above Yosemite Valley, near El Capitan. Photo: Ben Ditto.

An earlier version of this story appeared in the spring/summer 2019 issue of Yosemite Conservancy magazine.