Back in April 2018, we shared an inside look at an ambitious effort to digitize Yosemite’s collection of historical images before the hard copies fade or fall apart. A year and a half — and thousands of scanned photos — later, we’re back with more insights from the archives!

During the first year of this Conservancy-supported project, a group of Student Conservation Association (SCA) interns researched and organized thousands of images; the more than 6,500 photos they scanned are now publicly available on the NPGallery website. In 2019, our donors funded a grant to continue this important image-preservation initiative.

Working through the multitudinous images in the historic photo collection requires meticulous research, data entry and digitization. For each image, the intern team has to track down as much information as possible and determine whether or not the photo can be scanned and published. (They skip any images with copyrights or objectionable material.)

We checked in with some of the 2019 SCA interns to see what they’ve been up to in the archives!

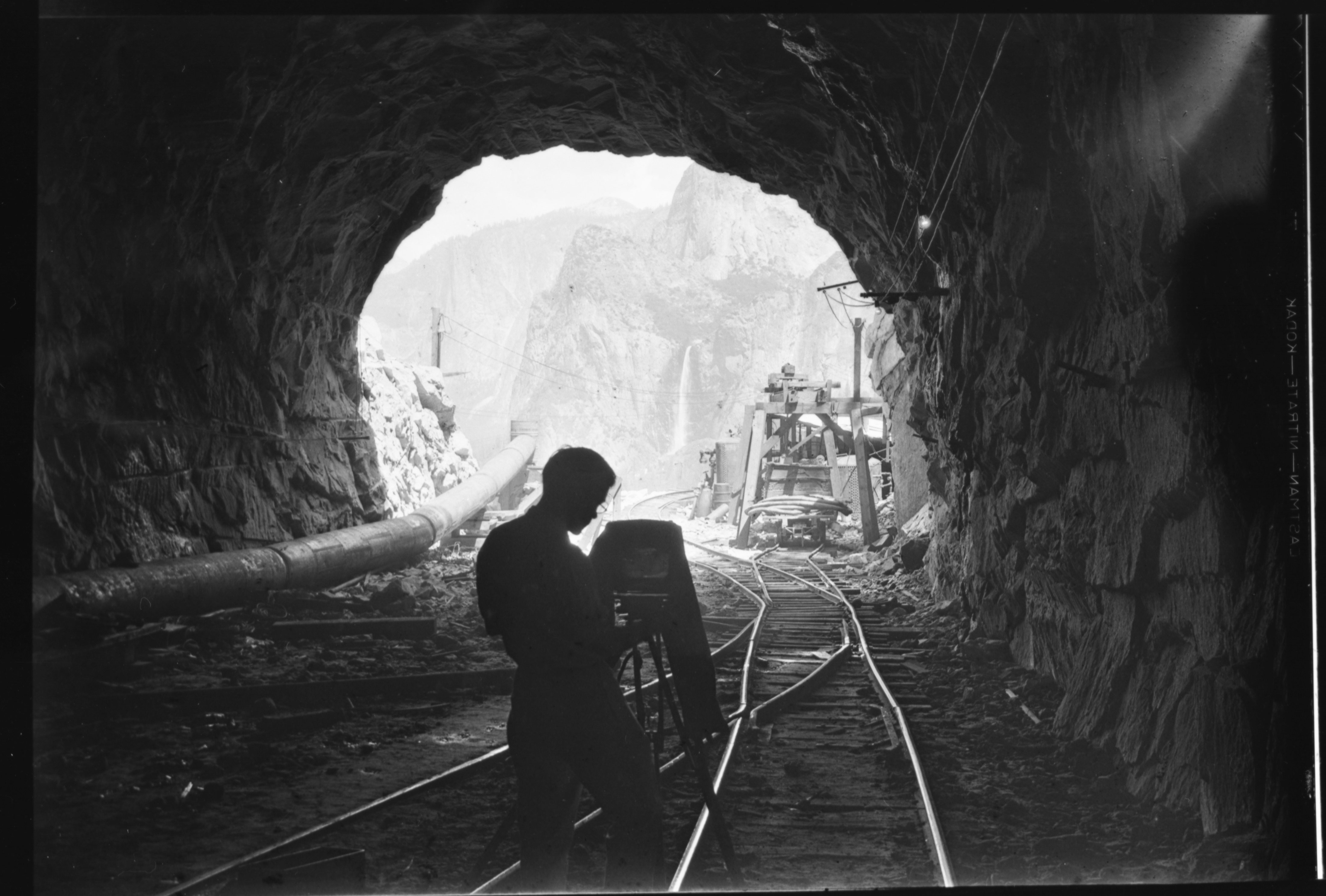

Shannon’s historic image pick: An inside look at the Wawona Tunnel, captured on May 29, 1931, by an unknown photographer.

Shannon, 24, hails from Greensboro, North Carolina, and studied at the University of North Carolina. As the metadata lead, she manages the digitization of the contextual information associated with the photos, such as the date, photographer and description. Often, that means transferring metadata from a physical photocard to a digital spreadsheet. That process is largely manual, Shannon says, but she’s been leveraging her knowledge of data analytics when possible, whether by applying VLOOKUP functions to find values in a spreadsheet or trying out an optical character recognition API to transcribe photocards.

Why do you think this project is important?

To me, this project serves two main purposes: preservation and accessibility. Both negatives and prints deteriorate over time, so digitizing them will preserve those images for future use. After scanning, we put the physical copy into cold storage to slow deterioration, but they still won’t last forever. Additionally, making these images available online will make them more widely and easily accessible. Rather than having to come to Yosemite, look through the photocards in the research library and request scans of particular images, researchers can simply search online and download images they want to use. This saves time for both researchers and Yosemite staff, while granting global access to anyone with an internet connection.

Tell us about some of the photographers behind the images you’re studying.

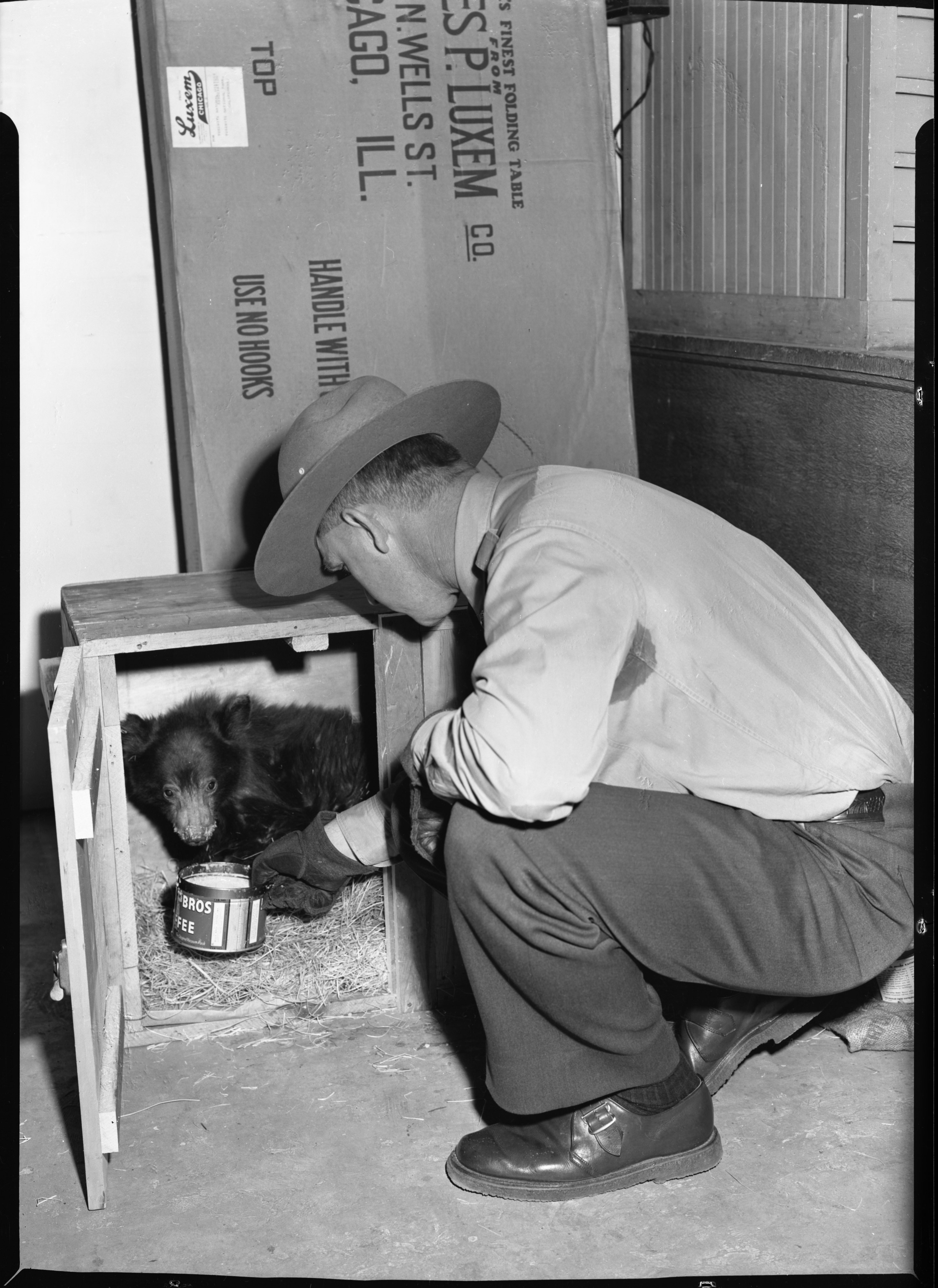

Most of the known photographers behind these images were park employees. Ralph Anderson, the official park photographer from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s, was by far the most prolific photographer in this collection. Douglass Hubbard, Yosemite’s chief naturalist from 1955 to 1966, and Robert McIntyre, another park naturalist in the 1950s, are two other names we see frequently. I have to pick McIntyre as my favorite after recently coming across photos of him with a bear cub that he rescued from starvation. One of my other favorites is A.E. Borell, who took many of the photos for the 1930s glacial surveys.

What was Yosemite like when these photos were taken?

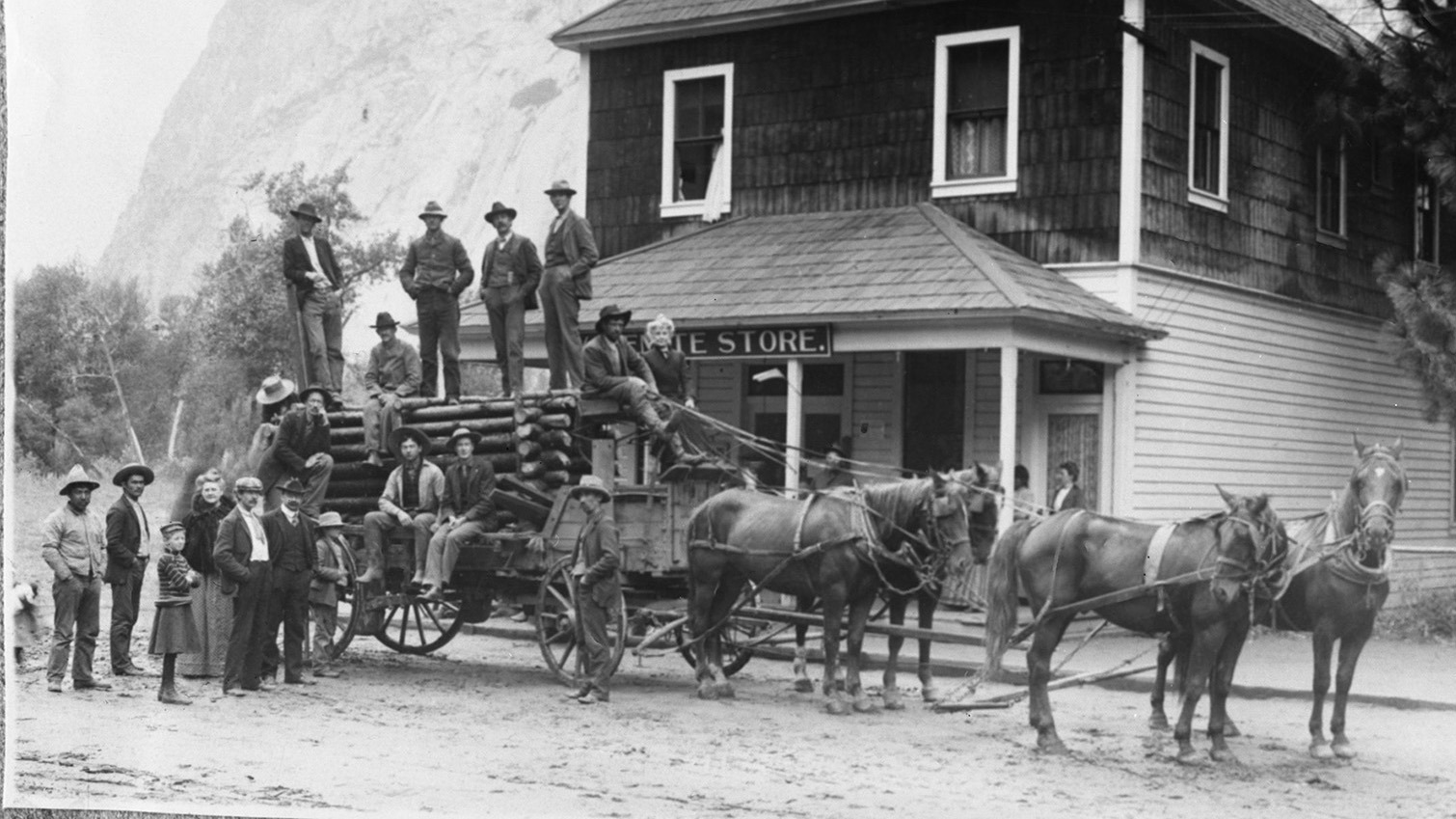

The photos we are digitizing primarily range from the 1920s to 1960s. Yosemite itself remains much the same now as during that period, but visitor activities (and fashions!) have certainly changed. In the earliest photos, getting to Yosemite involved a long stagecoach journey; now, millions of cars enter the park each year. Some early “traffic jam” photos look hilarious in comparison to the present day. Other photos I’ve seen that capture things not seen nowadays include the old annual fish fry celebrating the opening of Tioga Road, people feeding bears, and a man smoking a cigar while climbing Half Dome.

Kami’s historic image pick: Yosemite naturalist Robert McIntyre feeding a rescued bear cub in February 1950. Photo by Ralph H. Anderson.

Kameron (Kami), 22, from Glendora, California, is a student at Northern Arizona University. Since starting the internship in Yosemite, she’s learned a lot about the archives and the park, she says, including about legendary historical events and the popularity of rock climbing. As the project’s copyright lead, Kami is in charge of ensuring that the team doesn’t scan and publish any copyright-protected images. She conducts research on photographers who aren’t already catalogued in the available metadata to determine the status of their work.

Why do you think this project is important?

I think this project is important because it allows people all over the world to view these historic photos, through the online NPGallery. Digitizing the photos will make research easier and will let more people see how much has changed (or hasn’t changed) in Yosemite since the photos were taken.

Walk us through your average day in this internship.

Each day is different, but I’m typically working on inputting image metadata and doing copyright research. Every other day, I scan photos. Our goal for this year is to digitize around 6,500 photos, and we have already scanned more than 5,000. If the office is crowded, then I usually go down to the Bally Building (a collection storage facility) and work on processing or other projects.

How has this project affected your understanding of Yosemite?

This project has made me even more excited to go into the Valley or up to Tuolumne each weekend so I can see in real life what I’ve been seeing in photos. Working on this project has helped me learn about the history of Yosemite and actually see it happening. I know so much more about Yosemite now! It is a cool feeling when I’m walking around the Valley and I hear the names of things or people that I recognize from this project.

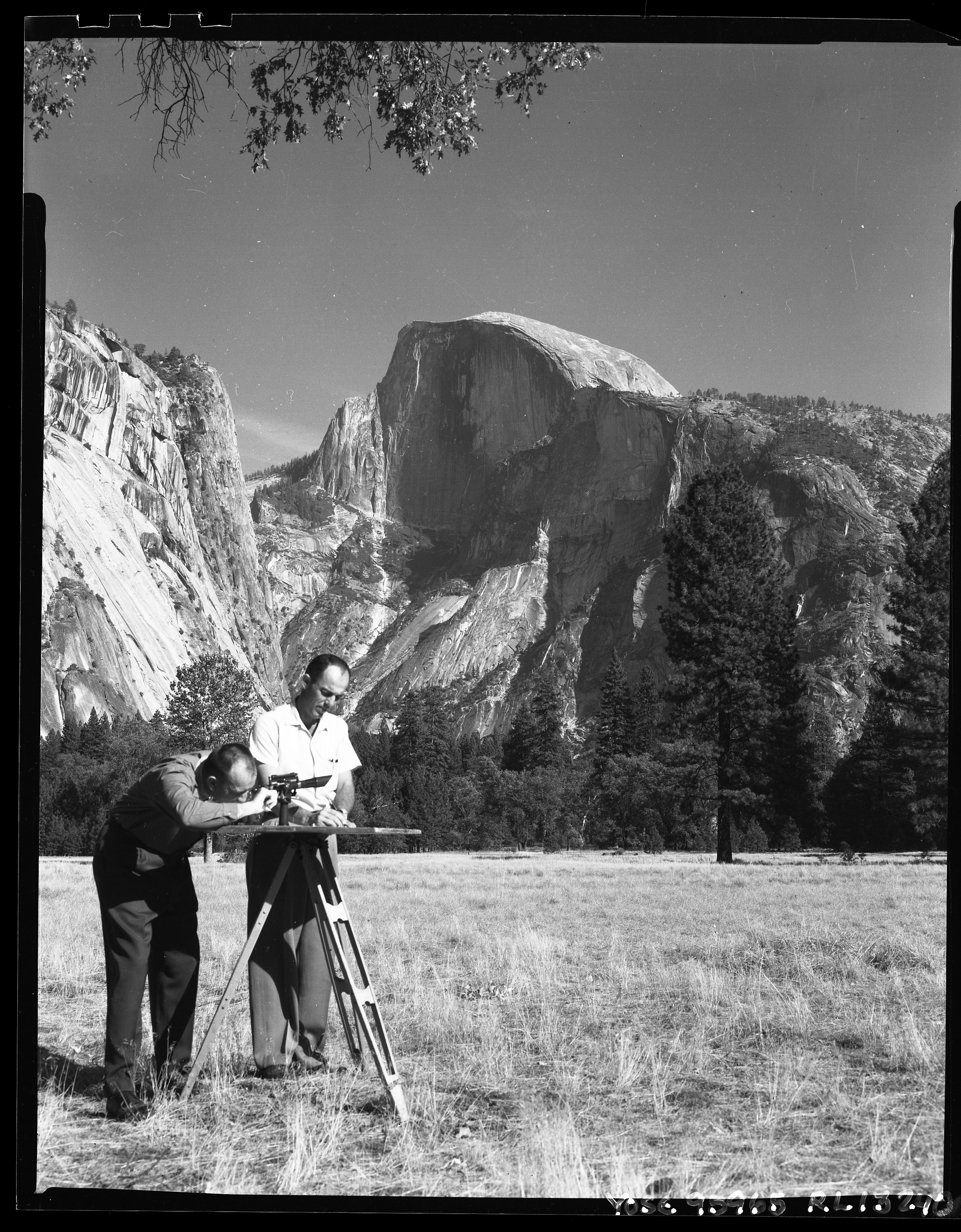

Cali’s historic image pick: Engineers at work in Yosemite Valley in October 1960, captured by Paul F. McCrary.

Cali, 22, is from the Santa Cruz Mountains, and is a graduate of California Polytechnic State University.

While the interns work together to scan the images, Cali, the project’s digitization lead, is responsible for ensuring the quality of the scans, making sure that all the images are digitized at high resolutions and properly cropped. While the three-minute wait for each scan to finish can drag on, Cali says one of the most rewarding parts of the internship is seeing the team’s progress as they work through the more than 30 boxes of historical images.

Why do you think this project is important?

This project is extremely important because it allows the public to access these photos from remote locations instead of traveling all the way to El Portal. These photos consist of a lot of different information and time periods in the park. Improve the public’s ability to find the photos and access the associated metadata is crucial in expanding the park’s outreach.

Why did you choose this internship?

I have wanted to work for the National Park System for a few years now and this position is in the field I’m pursuing. I am going to graduate school for library science and information studies with a concentration on archives in the fall. Being able to gain this experience is amazing, especially in a place like Yosemite.

Tell us about a person, place or event in Yosemite’s history that you’ve learned about through this project.

I have really enjoyed looking at the trail construction photos, including at places like the Mist Trail and around Hetch Hetchy. It’s amazing to look at the way in which trails were created and how challenging it must have been to construct them. I think a lot of visitors take these trails for granted.

When they’re not working through snapshots of moments from the park’s past, the interns are building their own Yosemite memories in the present. When we asked about their favorite Yosemite moments (so far), Shannon recalled running into a geology class from her alma mater on Lembert Dome: “It was fun to have that little unexpected taste of home and even hear a mini ‘Tar!’ ‘Heels!’ chant on the other side of the country.” Cali cited her first Yosemite snowfall — if you’ve ever visited the park when fresh flakes are sparkling against the pine and granite backdrop, you’ll understand why that moment stands out! And Kami chose a history-themed experience: getting a tour of the Yosemite Museum collections, where she saw paintings, baskets and other items, and enjoyed hearing stories that went along with the artifacts.

Back in the archives, the photos the SCA interns are painstakingly studying and digitizing carry their own stories from the park’s past. Inspiring images of iconic features that appear untouched by time. Entertaining glimpses of early 20th-century hiking apparel. Portraits of American Indians who lived in Yosemite Valley. Landscape photos of the Lyell and Maclure glaciers that, decades later, show how much ice has disappeared from those eastern Yosemite peaks.

We’re grateful to Kami, Cali, Shannon and the rest of the historic photos crew for their work on this project, and to our donors for supporting a second year of image digitization. If you’re in the mood for a little Yosemite time-traveling, head to NPGallery to browse thousands of vintage photos — and if you have historic images that you’d like to share, email us or get in touch with the Yosemite Archives team.