Which Yosemite animal do you most identify with? Take our quick quiz to find out!

Pick your…

… preferred place to hang out in the park:

a) Woodlands, especially conifer forests.

b) Boulder fields.

c) Meadows, with easy access to water.

d) Remote peaks.

e) Granite cliffs.

… hobby:

a) Singing.

b) Dehydrating food.

c) Sunbathing.

d) Climbing.

e) Sky-diving.

… typical winter plans:

a) Snow? No thanks. I’ll stay away until it warms up.

b) Hang tight and chow down (on dehydrated food, duh).

c) Find a cozy spot indoors. Nap a lot.

d) Stay in the mountains and tough it out.

e) Depends on where I’m wandering at the time.

… fashion sense:

a) Gray suit with a little flair.

b) Comfy and low-key..

c) Polka dots.

d) Shoes with good grip, and spikes.

e) Sleek and streamlined.

These small crooners are one of the many songbirds scientists have studied through a long-running MAPS (Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship) research program in Yosemite. Like other neotropical migratory birds, hermit warblers spend spring and summer in the Sierra, but head south for winter. These yellow-headed birds aren’t reclusive, despite their name, but can be hard to spot: They frequent conifer canopies high above the ground.

You might have better luck hearing, rather than seeing, these warblers. Listen for their sweet soprano notes overhead (for a preview, check out these recordings from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library). Read our “Songbird Science” post to see how researchers use data collected year after year in the park to study shifts in avian populations.

Mostly “b”: American pika.

Mostly “b”: American pika.

These compact rabbit relatives live high in the mountains of the western U.S., often staking out their territory on talus slopes, where their brown and gray fur helps them blend in with the rocky backdrop. During warmer months, pikas scamper around their high-altitude homes, foraging for the day’s food and gathering plants to create “hay piles” for leaner seasons. They remain active through the winter, even in the harsh High Sierra, relying on their piles of dried vegetation to keep their energy up as temperatures drop and snow falls. You’ll probably hear a pika before you see one — they communicate in loud, high-pitched, squeaky barks.

Mostly “c”: Yosemite toad.

Mostly “c”: Yosemite toad.

The females of this wonderfully warty California Species of Special Concern sport spots (hence the “polka dot” fashion sense); males are smaller and solid-colored. Yosemite toads, which are listed as federally threatened, are limited to the Sierra Nevada. Adults live in high-elevation meadows, usually within a few hundred feet of water, and warm their cold-blooded bodies by basking in the sun. When temperatures drop in autumn, they find places to hibernate — sometimes in other animals’ burrows.

Today, Yosemite toads are a rare sight in their namesake park, but scientists hope to help the species recover. In 2019, researchers are building on past Conservancy-supported toad surveys to study what helps the park’s large populations of this once-common amphibian thrive.

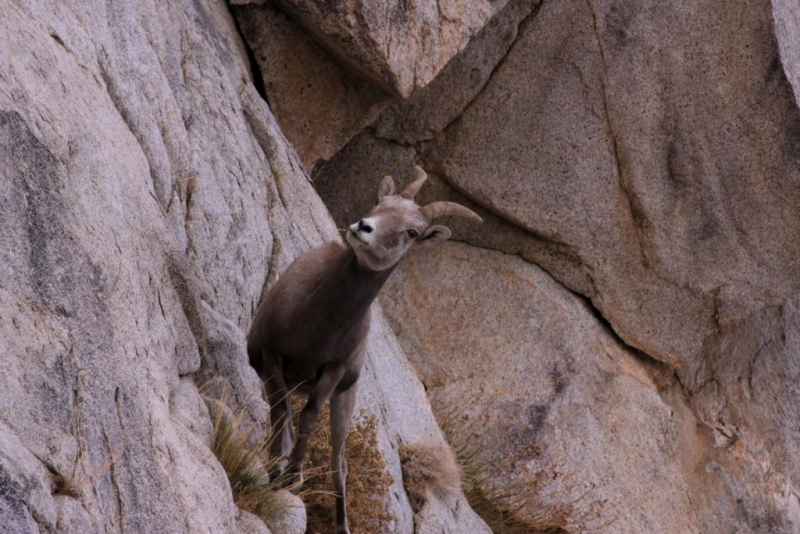

Mostly “d”: Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep.

Mostly “d”: Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep.

Meet the ultimate mammalian alpinist. This bighorn subspecies found only in California’s Sierra Nevada use rubbery hooves and impeccable balance to deftly navigate steep, rocky surfaces on high peaks in their eponymous range. They live in the mountains year-round, surviving on sparse vegetation and sometimes descending to lower elevations for the winter. Bighorns once climbed, leapt and foraged throughout the Sierra, but decades of hunting, disease and predation pushed them to the edge of extinction.

The endangered wild sheep’s future is looking bright thanks to years of interagency restoration work, including in Yosemite’s Cathedral Range, where biologists are working to ensure that a bighorn herd released in 2015 can thrive on its own.

Mostly “e”: Peregrine falcon.

Mostly “e”: Peregrine falcon.

These high-speed raptors nearly vanished from the U.S. in the mid-20th century, decimated by the effects of the then widely used pesticide DDT. Thanks to a DDT ban in the 1970s and decades of recovery work, however, peregrine falcons soared off the federal endangered species list in 1999.

Today, peregrines — whose name means “wanderer” — are found on every continent except Antarctica, gliding and stooping in forests and deserts, on coasts and in cities … and in Yosemite, where they nest on word-famous granite walls (and are the focus of a 2019 Conservancy grant). The park marks these aerodynamic acrobats as a year-round presence in Yosemite; elsewhere, they’re known for undertaking long migrations (including between the far northern tundra and South America). The next time you’re in the Valley, see if you can spot a dark streamlined shape launching from a cliff ledge — and if you’re a climber, check for seasonal route closures implemented to protect peregrine nests on the walls.

Didn’t find a match? That’s not surprising: Yosemite supports hundreds of species of birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians, plus innumerable butterflies, beetles, bees and other invertebrates — way more than we could fit in a quick quiz!

Along with that incredible animal diversity, you’ll find a variety of ways to learn about wildlife in the park. Pick up a field guide from on of our bookstores, join a naturalist-led birding walk or Junior Ranger talk, or spend a few days in the wilderness on a guided backpacking trip. Maybe you’ll find your wildlife match when you read about an alpine butterfly, listen to naturalist’s insights about great gray owls, or watch (from a safe distance!) a bobcat sauntering through a forest —and maybe not. Regardless, whenever you take time to learn a little more about animals in Yosemite, you’ll deepen your connection to the park and its soaring, singing, buzzing, bleating, haying, sunning, swimming tapesty of wild life.

![Photo: USFWS/Frode Jacobsen [CC-BY-2.0]](/wp-content/uploads/d7/useruploads/blog_animal-id_hermit-warbler_usfws-frode-jacobsen_cc-by-2.jpg)