Many of the park’s best-known trails trace the floor and edges of Yosemite Valley: You might know the Mist Trail’s steep stone steps, or the Valley Loop Trail’s quiet, shady stretches. Most of Yosemite’s approximately 800-mile trail network, however, extends far beyond those well-trodden paths. Thanks to support from our donors, park crews have been able to complete vital work on trails throughout the Yosemite Wilderness.

That essential work is accomplished by the park’s renowned trail crews and, often, the young adults of the California Conservation Corps (CCC), who spend several months learning and working in remote parts of the backcountry. You can see the results of their work all over the park — and today, we’re looking beyond the floor of the Valley to see how Conservancy-supported projects have helped less-traveled trails, from Tenaya Canyon to remote peaks and passes.

Beyond the Valley Floor

Not far from Yosemite Valley’s famous cliffs and waterfalls, you’ll find an array of trails leading through meadows and forests, along creeks, up canyon walls and to breathtaking views. In spring and summer, one of the park’s CCC crews works its way from the Valley floor, up to the rim and out into the far reaches of the Merced River watershed.

Where: Snow Creek Trail

When: Annually

Work accomplished: Much of Merced-drainage CCC crew’s early-season work takes place on the Valley floor, but corpsmembers also venture up granite walls to spruce up the Snow Creek Trail, which climbs the side of Tenaya Canyon.

Often, they work on the trail’s notorious switchbacks — a heart-pumping stretch of more than 100 steep zigzags — where they repair damage from winter storms and rockfalls to ready the route for hikers and backpackers.

Where: Mt. Starr King and Mono Meadow

Where: Mt. Starr King and Mono Meadow

When: 2018

Work accomplished: In July 2018, after wrapping up their trail tasks in the Valley, a CCC crew pitched their tents near Illilouette Creek, setting up a basecamp for backcountry restoration work. In addition to repairing and building rock features to make creekside trails safer and more durable, they cleared dense brush and whitethorn to widen a dozen miles of overgrown hiking terrain, including along the Starr King Trail. (Meanwhile, their peers working in the northwestern part of the park turned their attention to trails in the Tuolumne River drainage, including on Mt. Gibson, north of Hetch Hetchy.)

Where: Lost Valley

When: 2016

Work accomplished: When melting snow and stormwater carved a deep rut across the trail through Yosemite’s granite-flanked Lost Valley, tucked between Little Yosemite Valley and Echo Valley, the park’s restoration program took action. After setting up their summer base camp near the Merced River, a 2016 CCC crew spent five weeks repairing the chasm and creating a durable drainage system designed to let water flow through the valley without eroding the trail.

On the Outskirts

Yosemite’s more remote trails don’t receive as much foot traffic as their well-traveled peers in the Valley and elsewhere, but years of hiking and harsh weather take a toll. To restore wilderness trails in far-flung parts of the park, crews often spend weeks in the backcountry, living in a base camp and hiking to and from their work sites each day.

Where: Donohue Pass

Where: Donohue Pass

When: 2012

Work accomplished: After a relatively dry winter, a lower than usual snowpack allowed a 2012 CCC crew to spend part of their season working on a particularly rough stretch of the Pacific Crest/John Muir Trail near Donohue Pass, on Yosemite’s eastern boundary. The crew focused on a section of trail bounded by a footbridge and the top of the pass, and addressed issues such as slick rock, deep ruts, jagged boulders, loose soil and erosion.

Per usual, the corpsmembers relied on naturally available building materials — the Sierra Nevada’s ample boulder supply — for their trail projects. Moving massive rocks isn’t an easy task, but the crew came prepared with a “highline” system to hoist and pull rocks. As summer warmed the high country, they built stone steps and walls, made the official trail easier to follow (while restoring impacts from informal hiker-generated paths), and diverted water away from the trail.

Where: Virginia Canyon and Summit Pass

When: 2017

Work accomplished: As snowmelt from the exceptionally wet 2016-17 winter spilled through creeks and seeped into soil, a CCC crew settled into their summer home in Virginia Canyon, in the northeastern Yosemite Wilderness. (Before moving to that backcountry base camp, the crew had spent several weeks marooned on Mt. Gibson when spring runoff created a temporary island.) As they worked through and around the canyon, they focused on repairing damage and improving drainage by building terraced steps, causeways and water breaks; repairing ruts; and narrowing washed-out sections of trail.

Where: Red Peak Pass

When: 2005–2011

Work accomplished: Over several seasons, park crews transformed 12 miles of the trail that leads over Red Peak Pass, in the southern Yosemite Wilderness. The goal: Repair and restore the deteriorating trail to improve hiking conditions, protect surrounding habitat and prevent erosion.

Using the hallmarks of Yosemite trail work — including skillful drystone masonry and an incredible attention to detail — crews constructed sturdy walls and water-diverting bars, built steps and shaped switchbacks to ease travel on steep grades and slippery rock, and restored trailside alpine meadows.

Relocation & Consolidation

Sometimes, trail work goes beyond restoring an existing route. Hard-to-follow, poorly drained or nonexistent trails can lead to damaged ecosystems and networks of “social trails,” informal paths that aren’t always safe or environmentally sustainable. In the cases below, park crews focused on helping hikers and habitats alike by channeling people (and horses and mules) onto appropriately located trails.

Where: Mt. Dana

When: 2011–2013

Work accomplished: At least seven special-status plant species dwell on the upper slopes of Mt. Dana, Yosemite’s second-tallest peak. Located just a few miles from the Tioga Pass Entrance, the plants’ rocky alpine home has attracted generations of hikers. Over time, those summit-seekers left behind a tapestry of informal trails that threatened critical plant habitat.

Starting in 2011, park crews set out to save the plants and secure a safe, sustainable route for Mt. Dana hikers. After mapping vulnerable plant populations and social trails, crews got to work: They identified and formalized a new trail to the summit, strung together from existing paths that hemmed plant habitat; removed the remaining hiker-generated trails (more than 16,800 linear feet in total); restored natural topography by loosening soil and carefully placing rocks on the slopes; and added official cairns to make the designated route easy to spot. Lower down on the mountain, where hikers pass by flower-dotted meadows and lodgepole pines, they added switchbacks and steps to make the trail more visible and durable.

Where: Lyell Canyon

Where: Lyell Canyon

When: 2012–2018

Work accomplished: Over decades, hikers and horses trekking through Lyell Canyon on the Pacific Crest/John Muir Trail left a mark. As boots and hooves stepped off the trail to avoid mud and pooling water, they crushed plants and etched deep ruts into the meadow.

To protect the canyon’s wetland habitat and create a more enjoyable (and less soggy) hiking experience, trail crews didn’t just repair the ruts: They relocated the trail. Between 2012 and 2018, crews shifted more than 11,400 feet of trail to better-draining parts of the canyon and erased the footprint of the former route.

Where: Various climbing trails

When: 2012–Ongoing

Work accomplished: Yosemite’s granite walls and domes make the park a world-renowned rock-climbing destination. The climber’s challenge, however, doesn’t always start and end on the rock. Before and after a climb, you must get to and from the cliff, column or spire … and there isn’t always a clear path.

In 2012, with support from a Conservancy grant, the park initiated a restoration effort focused on formalizing and improving approach and descent trails for popular climbing routes. Since then, climbing rangers, trail experts and hundreds of volunteers have worked to create, consolidate and/or repair safe, habitat-friendly access trails for climbing routes throughout the park, from famous features like El Capitan and Cathedral Rocks to Five Open Books (near Yosemite Falls), Daff Dome (Tuolumne Meadows) and Phobos/Deimos Cliff (near Tenaya Lake).

All these trail projects, and so many more, have been made possible through the generous support of people who love the park. Wherever your Yosemite travels take you — to waterfall spray zones, quiet forests, rocky alpine slopes, remote passes or anywhere else — take a moment to look for evidence of trail crews’ hard work: drainage features, carefully shaped switchbacks, rock walls and steps, bridges and boardwalks.

If you appreciate Yosemite’s trails, and the crews that keep them in top shape, we hope you’ll consider supporting restoration work in the park. Take a look at our current grants to learn more. See you on the trails!

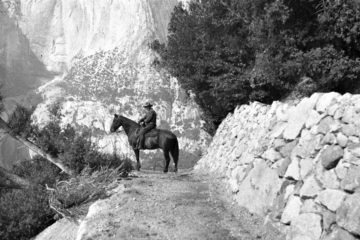

Above: A hiker in the Red Peak Pass area, in the southern Yosemite Wilderness. Photo: Josh Helling