Every year, our supporters help fund important trail restoration work in the park — including, often, on “legendary trails” in Yosemite Valley.

What makes a trail legendary? A storied past? Epic sights? Heart-pounding switchbacks that take on near-mythical status in tales told and retold about memorable hikes?

For generations, long before today’s popular paths took shape, American Indians followed trails in and across the Sierra. As sightseers made their way to Yosemite in the 1800s, a network of tourist-oriented trails emerged. Some of today’s famous trails were already in place by the time the 1864 Yosemite Grant Act set aside Yosemite Valley (and Mariposa Grove) as protected lands to be managed by the state of California; others started as 19th-century toll trails chartered by the grant’s commissioners (and built by entrepreneurs). Several feature arduous climbs, others stick to gentler terrain, and some bear remnants from years as paved equestrian routes.

All offer memorable views of one of the world’s most famous landscapes — and all benefit from the work of Yosemite’s top-notch trail crews, often made possible through donor-funded grants.

Vernal Fall/Nevada Fall Trail

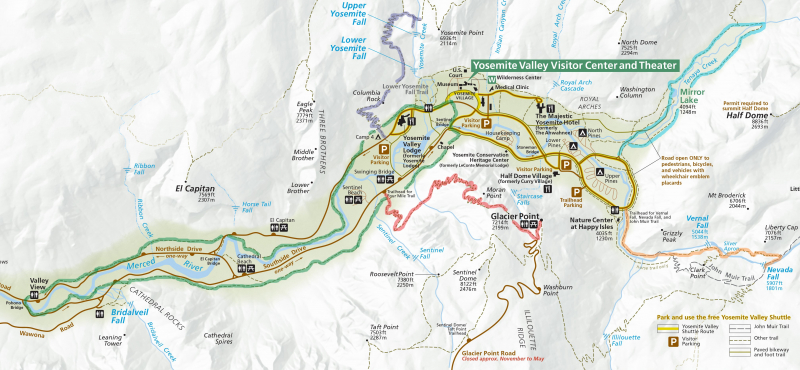

Location: Eastern Yosemite Valley. Look for the trailhead near Happy Isles.

Length: 2.7 miles (one way, to the top of Nevada Fall).

Leads to: Vernal and Nevada falls.

Legendary for: Steps and spray.

A trail to the top of Vernal Fall along the Merced River was already established by the mid-1860s. The Yosemite Grant commissioners added a bridge across the Merced River at the top of Vernal Fall, to help travelers reach nearby Nevada Fall. By the 1870s, the trail featured a toll house (at “Register Rock”) and a hotel (at the base of Nevada Fall). Those structures are long gone, but the basic route — and its notoriously steep terrain — remain.

After hiking uphill from Happy Isles along the north side of the Merced (the original trail followed the south bank), crossing a footbridge and stepping onto the Mist Trail, you’ll climb more than 600 stone steps beside Vernal Fall, and then continue uphill for another mile and a half to the top of Nevada Fall. As you climb, you’ll get to see the power of the Merced River as it drops and churns into Yosemite Valley, carrying snowmelt from its high-country headwaters.

Enjoy the refreshing, often rainbow-laced mist, and see if you can spot the spray-zone plants that thrive in the damp habitat beside the falls. (Don’t look too closely: Stay safe by staying on the trail, far from the water’s edge and behind safety railings.)

Yosemite Falls Trail

Location: North wall of Yosemite Valley. Look for the trailhead near Camp 4.

Length: 3.6 miles (one way).

Leads to: The top of Yosemite Falls, the tallest waterfall in California (and among the tallest in the world).

Legendary for: Steep climbs and sweeping views.

Nineteenth-century Yosemite trail-builder John Conway constructed the trail to the top of Yosemite Falls (and beyond, to Eagle Peak) in the 1870s. He operated the trail as a toll route before selling it to the state of California in 1885.

Now, as in the late 1800s, the trail features unrelentingly steep, rocky terrain — and its rich scenic rewards. The challenging trek to the top yields jaw-dropping views of Valley icons, including Half Dome and Sentinel Rock, plus the chance to hike alongside Upper Yosemite Fall, feel the spray as the water careens downward and marvel at the modest creek that fuels the cascade.

(Note: You can enjoy eye-popping sights without tackling the full 7.2-mile round-trip route, thanks to the views from Columbia Rock, about a mile from the trailhead.)

Four Mile Trail

Location: South wall of Yosemite Valley. Look for the trailhead off Southside Drive, between Swinging Bridge and Sentinel Beach.

Length: 4.8 miles (one way).

Leads to: Glacier Point.

Legendary for: Strenuous switchbacks, panoramic views and a slightly misleading name.

John Conway’s trail-building wasn’t limited to the north wall of the Valley. Entrepreneur James McCauley hired Conway to lead construction on the Four Mile Trail, which was completed in 1872. The original trail covered the distance from the Valley floor to Glacier Point in about 4 miles; a half-century later, park crews rerouted sections of the trail, stretching the length closer to 5 miles.

From Southside Drive, the trail climbs below Sentinel Rock, jags east, then zigzags up the wall, passing Union Point and Moran Point on the way up to Glacier Point.

As you hike, you’ll gain more than 3,000 feet of elevation — so take plenty of breaks to enjoy the views. Get a close-up look at Sentinel Rock, gaze across the Valley at Yosemite Falls and El Capitan, and see the Sierra spread out for miles around you from Glacier Point.

Mirror Lake Trail

Location: Eastern Yosemite Valley. Look for the trailhead near the Pines campgrounds.

Length: 1 mile to the lake; 5 miles for a full loop around the lake.

Leads to: Mirror Lake.

Legendary for: Reflections and transformation.

Like the trail to Vernal Fall, the Mirror Lake Trail was already in place by the mid-1860s. Today, you can take a mile-long stroll on a paved trail to the lake or extend your hike to a quiet 5-mile loop that parallels Tenaya Creek as it flows through Tenaya Canyon.

In spring, you’ll walk beside the fast-flowing creek as it courses toward the Valley, pools at the base of Half Dome (where you can admire Mirror Lake’s famed reflections of surrounding scenery, including the prominent prow of Mount Watkins), and dances downstream to join the Merced.

As the water slows in summer and autumn, “Mirror Lake” often transforms into “Mirror Meadow” — still a lovely hiking destination, but not as useful as a swimming hole.

Valley Loop Trail

Location: Valley floor. You can join the trail at several points, though a popular start and end point is near Lower Yosemite Fall.

Length: 13 miles

Leads to: Numerous serene, often scenic spots around the Valley.

Legendary for: Being flat and flexible.

The Valley Loop Trail does just what the name implies: creates a hikeable loop around the floor of Yosemite Valley. The modern route got its name long after other “legendary” trails in the Valley, but follows remnants of early trails and wagon roads.

Sections of today’s loop were once called the “bridle” trail, a nod to paths and roads originally built with horse travel in mind. (Before the mid-1870s, there were roads on the floor of Yosemite Valley, but none leading in and out; tourists arrived on foot or horseback. Galen Clark — and later James Hutchings — used mules to pack carriage parts into the Valley to offer people a wheeled travel option during their stay.)

Today, the loop offers opportunities to experience parts of the Valley that you might overlook if you spend all your hiking time climbing steps and switchbacks up the cliffs. Starting at Lower Yosemite Fall and heading west, you’ll hike along the base of famous formations like El Capitan and Cathedral Rocks, see year-round and seasonal waterfalls, and wander by mossy boulders, leafy trees and the meadow-flanked Merced River.

Since the loop has multiple entry and exit points, you can choose your distance and destination: Hop on the trail for a short stretch, create a half-loop, or enjoy the full 13-mile hike over relatively flat, gentle terrain.

For decades, the Valley’s celebrated trails have drawn hikers from around the world. On busy summer days, thousands of people follow these trails to wondrous views, meadows and waterfalls. All those steps, coupled with occasional rockfalls, floods and other natural events, leave a mark. That’s where restoration projects come in: Crews repair boardwalks and bridges; install sustainable, durable trail tread; shore up switchbacks and steep slopes; remove fallen trees, boulders and other obstructions; add signs to help hikers find their way; and more.

Donors’ support has helped keep Yosemite’s legendary trails in top shape — and will help ensure they can continue to welcome hikers for years to come. To learn more about trail restoration projects you can support in the park, take a look at our current grants.

Trail Tips:

- Check weather and trail conditions before you start. Even in late spring, snow and ice may linger on some open trails. Talk to a ranger or one of our volunteers to get the latest information, and respect any trail closures or restrictions.

- Bring plenty of water and snacks, plus a headlamp or flashlight in case you end up on the trail after dark.

- Stick to formal trails. Don’t shortcut switchbacks, and stay far back from rivers, creeks and waterfalls.

- Take time to enjoy the sights, sounds and smells. Look for seasonal scenery, like ephemeral waterfalls or autumn foliage; listen for birdsong, woodpeckers and flowing water; take in the scents of pine, damp earth and fragrant flowers.

- Read our “Trail Tips” blog, featuring advice from our resident naturalist!

Above: Gabriel Sovulewski, who spent more than 30 years working in Yosemite in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, poses on horseback on the Four Mile Trail (circa 1930). During his decades in Yosemite, including many years as park supervisor, Sovulewski oversaw construction and improvement projects on trails throughout the park. Photo: Yosemite Historic Photo Collection.

Want to learn more about trails in Yosemite Valley and beyond? Check out Linda W. Greene’s “Yosemite: the Park and its Resources” (1987).