by Holly Yu, Communications Intern, Yosemite Leadership Program Summer Internship 2024

I first learned about the peregrine falcon while watching Wild Kratts as a kid. They left my mind until I had a wonderful opportunity this summer to attend a peregrine falcon survey with Alexandria Walker, the Raptor Surveyor for Yosemite National Park.

We spent the day visiting some of the nesting areas in Yosemite. Looking through a spotting scope, we observed this year’s nestlings walking and sliding around on the cliff ledges thousands of feet above the Valley floor. Smaller than a hawk or eagle, but just as fierce and impressive, they are easily my newfound favorite bird.

It is crazy to think there was a chance I would not be able to experience this because the species was once federally endangered. While staring at the wall and waiting for movement from the adorable fluffy nestlings, Walker shared the history of Yosemite’s peregrine falcons and the collaborative effort that brought their numbers back up. It is an amazing story that everyone who gets to look up at the climbers on those towering cliffs should know about.

What is a Peregrine Falcon?

Commonly known as the fastest animal on earth, peregrine falcons are about the same size as crows. They eat almost any bird they can get their talons on and in Yosemite they specialize in white throated swifts and band-tailed pigeons. Their long, sculpted wings and strong feet allow them to hunt prey both bigger and smaller than them. They are aerial hunters, catching their prey directly out of the air.

Peregrine Falcons in Yosemite National Park

The cliffs of Yosemite are home to many plants and animals. While looking up at the walls of El Capitan and other cliff faces, you might see a dot speeding through the air. They nest on the side of cliffs and hunt at their impressive speeds, diving up to 200 mph, making it difficult to keep up with your eyes.

In addition to their primary nesting location, peregrines will maintain 1-6 alternate nest sites and may change which nests they actually use year to year. Walker will update closure letters as she determines which nest site is in use in a given year. Peregrine falcons are found all over the world today but in the 1940s, they disappeared from the cliffs of Yosemite.

Learn more about peregrine’s life on Yosemite cliffs in the recent article, “Vertical Research.”

Endangered Eggs

Why were peregrines listed as federally endangered? Due to a pesticide used on crops called dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, better known as DDT, the eggshells of organisms up and down the food chain — from insects to small birds and birds of prey — became thin because of bioaccumulated DDT.

When peregrine parents incubated their eggs, the eggs would crack thus causing mortality to the chick. This led to population decline and their federal listing as endangered under the newly minted Endangered Species Act in 1973.

Climbers, Scientists, and the Return of Yosemite Peregrines

Thanks to the 1972 ban of DDT, a team of climbing biologists, the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group (PBRG), and funding from the Peregrine Fund and Yosemite Conservancy, peregrine falcons were able to make a comeback.

After a 36-year absence, a pair of peregrines were found nesting by climbers on El Capitan in 1978. This collaborative partnership was formed to help save the species in Yosemite.

Biologists from Santa Cruz PBRG and Yosemite National Park worked together with climbers to ascend the cliffs to access known nests, swap out the DDT effected eggs for wooden dummy eggs, bring the eggs back down the cliff to incubate in labs, and then climb back up to swap the dummy egg with chicks that hatched successfully.

Thanks to conservation efforts in Yosemite and around the country, peregrine falcons were delisted from the federal endangered species list in 1999 and the California endangered species list in 2009.

Learn more about the story of their return in the Conservancy funded video, “A Story of Hope” or the article “Protecting Peregrines.”

Present Research on Yosemite Peregrines: New strategies for a new chapter

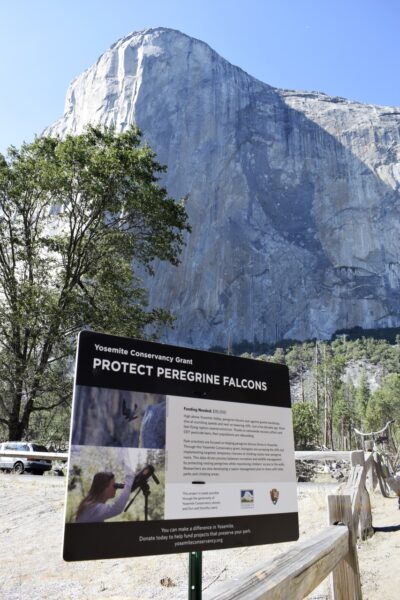

Although peregrine falcons are no longer federally endangered, they are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA). The protection of the legendary peregrine falcon continues to be possible with support of Yosemite Conservancy donors.

In 2024 with donor-support, researchers maintain daily peregrine surveying, nest monitoring, implementation of climbing closures adjacent to active nests, and regularly update protection measures at active peregrine nest sites during the breeding period.

According to Walker, “Peregrines have been recorded being most affected by prolonged disturbance above and in direct view of their nest.”

The goal of these closures is to minimize nest disturbance and potential nest abandonment from cliff recreation. The closures also help climbers avoid aggressive interactions from protective peregrine parents.

In many climbing areas across the country wildlife biologists institute “blanket climbing closures.” These often covered a broad cliff area for a longer period of time — up to 5 months. This is usually the protocol for climbing areas that are not actively monitored, often times due to lack of resources. With the extreme popularity and number of climbing routes across Yosemite, an “adaptive climbing closure” approach was deemed the most appropriate method of action.

Since 2009, one of the innovations that the Yosemite Raptor Protection Program has initiated is an iterative approach to climbing closures. Today, this program allows wildlife biologists to work alongside Climbing Rangers to promote awareness and support of nesting raptors within the climbing community – and ensure that nesting raptors have all the space they need.

“Yosemite’s daily raptor monitoring and adaptive approach to implementing and lifting climbing closures is unique among other land agencies. By observing the birds closely and studying individual pairs sensitivity to disturbance and nesting chronology, we can delineate smaller closure areas, shorten or extend closure durations, and implement amendments to the closure list as needed throughout the season ,” explains Walker. “These defined closure areas are proposed by a committee of Biologists and Climbing Rangers. Climbing patrols are performed to assess pair tolerance and help determine the size of the closure.”

We can update climbing closures regularly throughout the season because every day we are observing the peregrines’ behavior and assessing their nesting status.. This way, both peregrine falcons and climbers can maximize their enjoyment of the cliffs of Yosemite.

“The current relationship with the climbing community is very positive. By utilizing our adaptive closure approach, we have fostered trust while promoting climber access,” shared Walker.

2024 Nesting Status of Yosemite Raptors

2024 Nesting Status of Yosemite Raptors

“2024 was a great year for peregrine falcons,” commented Walker when sharing this year’s survey results. There were 15 peregrine nests confirmed and 23 young. This year’s survey effort included 43 cliff sites, 63 historical nests, and 220 survey hours.

How Climbers Can Enjoy Yosemite’s Cliffs and Respect the Yosemite Peregrines

If you are a rock climber and would like to help protect Yosemite’s peregrine falcons, check active closures before you go out climbing. The website is updated frequently based off the daily surveys of the nests by wildlife biologists.

There is a chance you may encounter an aggressive peregrine or find a nest while climbing or hiking. Aggressive behavior includes bluff charging or dive bombing. If this happens, immediately descend or leave the area and report the sighting to yose_peregrines@nps.gov with GPS coordinates and photos.

Photo descriptions and credits:

Adults soaring past Half Dome by James McGrew

Peregrine and nestlings by Craig Himmelwright

Peregrines in mock combat courtesy of NPS

Hiker reading closure sign by Keith Walklett

Yosemite Conservancy project sign in front of El Capitan by Yosemite Conservancy/ Ryan Kelly