A version of this story appeared in the Autumn/Winter 2015 issue of the semiannual Yosemite Conservancy magazine.

Yosemite’s nearly 800 miles of trails offer access to popular destinations, such as Vernal Fall and Glacier Point, and to far-flung, far-less-visited peaks and lakes. In the mood for a short stroll? Explore part of the Valley Loop Trail, or wander along the shore of Tenaya Lake. Up for a longer jaunt? You could easily spend a week or more backpacking in the Yosemite Wilderness, immersed in the Sierra landscape dozens of miles from the nearest road.

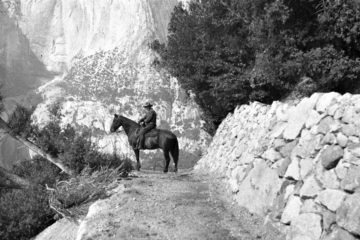

Harsh weather, and years of footsteps, can take a toll on trails. Our donors have supported trail restoration projects throughout Yosemite, funding projects that create safe and enjoyable hiking experiences, protect habitat, and help wilderness travelers – including mounted patrol rangers and mule train leaders – navigate the backcountry.

A lot of that donor-supported restoration work has focused on giving California Conservation Corps members in their late teens and early 20s the chance to work alongside Yosemite’s top-notch trail experts. (The CCC, a state agency established in 1976 and modeled in part on the 1930s Civilian Conservation Corps, is the oldest and longest-running conservation-corps program in the U.S.) During their season in Yosemite, CCC crew members learn and apply restoration skills to complete much-needed work on park trails.

A lot of that donor-supported restoration work has focused on giving California Conservation Corps members in their late teens and early 20s the chance to work alongside Yosemite’s top-notch trail experts. (The CCC, a state agency established in 1976 and modeled in part on the 1930s Civilian Conservation Corps, is the oldest and longest-running conservation-corps program in the U.S.) During their season in Yosemite, CCC crew members learn and apply restoration skills to complete much-needed work on park trails.

Much of the vital work that National Park Service and CCC crews perform in Yosemite is a mystery to the everyday hiker. “People don’t see a lot of what we do,” Yosemite Trails Supervisor Steve Lynds told us. “They only see the top layer.”

To understand what goes into shaping Yosemite’s trails, we asked Lynds, who got his start through the California Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1991, and Mark Scrimenti, a 2014 CCC alum and current member of the Conservancy’s wilderness team, about life on the park’s backcountry crews. We invite you to step into their boots, and imagine you’re spending a season on the trails.

Here’s what your day might look like:

4:30 am | Wake up. Head to the makeshift camp kitchen, and eat breakfast prepared by the on-site chef. Having a cook on the crew (a norm in Yosemite, but not necessarily in other parks) helps keep workers energized through long seasons of intense 10-hour days.

7:00 am | Hike to the work site (sometimes several miles), carrying tools such as shovels, hammers and “rock bars,” which work as levers when wedged under boulders. Spend the morning removing brush and logs, digging trenches (swales) to divert rain and prevent erosion, or building a boardwalk to protect plants and preserve water flow.

Or dive into what Scrimenti calls the “coolest, toughest” part of trail restoration: rockwork. Yosemite’s crews practice dry-stone masonry, which means they build sturdy structures without mortar, drawing instead on patience, physical strength, and newly learned skills passed down by experienced supervisors.

12:00 pm | Refuel with a lunch break. You’ll need the energy — it’s time to move rocks!

12:00 pm | Refuel with a lunch break. You’ll need the energy — it’s time to move rocks!

Yosemite’s crews use native materials. That means finding granite boulders — sometimes the size of cars — and breaking them into manageable pieces, then moving them using your own strength (hug, lean, roll), rock bars or even pulley systems. Trail workers often tackle these tasks alone, but major moves require multiple hands.

Basic rules for working with rock include building on a strong foundation and offsetting stones to avoid creating vulnerable vertical seams. Rockwork is like a jigsaw puzzle. Carefully chisel the stone into the shape you need. Chipped off too much? Find a new rock.

5:00 pm | Hike back to camp. Bathe in a lake or river. Eat with your crew. Celebrate your progress: Placing two rocks in a single day is cheer-worthy. To build a rain-diverting waterbar, Scrimenti spent six weeks moving and meticulously arranging fewer than 20 rocks — about one every two days.

As hikers, we often notice impediments or issues on a trail – a soggy section that leaves our boots soaked, or a steep, eroded uphill stretch. As Lynds pointed out, it’s easy to miss the signs of a crew’s careful work. How often do you observe water flowing off a trail, rather than pooling in the middle, or take note of sturdy steps easing an ascent?

As hikers, we often notice impediments or issues on a trail – a soggy section that leaves our boots soaked, or a steep, eroded uphill stretch. As Lynds pointed out, it’s easy to miss the signs of a crew’s careful work. How often do you observe water flowing off a trail, rather than pooling in the middle, or take note of sturdy steps easing an ascent?

If you look closely on your next Yosemite hike, you’ll see traces of the extraordinary diligence and precision that make the park’s crews and trails stand out. Their work is visible in the steps on the Mist Trail, the stone walls near Yosemite Falls, countless smooth high country switchbacks, and much more.

Over the past three decades, hundreds of CCC members have had the chance to learn and work on Yosemite’s trails. This year, thanks to our donors, two more CCC crews are spending a season in the park. With each predawn wake-up and painstaking rock placement, they’re gaining the skills and experience necessary to keep trails in top shape – and developing a deeper appreciation for the value of stewardship in, and far beyond, Yosemite.

Thanks for reading, and happy trails! (Before you go, be sure to check out our current projects to see how your gifts can make a difference for Yosemite’s trails.)

Trail Terms

(to impress your friends on your next hike…)

crush: Small, angular pieces of rock used to fill space around rock structures. Rounded rocks or gravel can act like slippery ball bearings, but angular crush, which is created by smashing larger rocks and is a standard material on almost any project, is crucial for stabilization.

drainage feature: An existing or constructed element that helps keep water off a trail. Common features include swales, naturally occurring or excavated dips that prevent water from collecting (armored swales are reinforced with rocks); and waterbars, which combine a broad dip in the trail and an angled barrier a few feet downslope.

dry stone: A method of building walls and other rock features without using mortar as an adhesive.

griphoist: A portable, manually operated hoisting device with a strong wire cable, used to move rocks and logs weighing thousands of pounds.

plug and feathers: A technique used to split rocks using sets of three tools: a metal wedge (the plug) and two curved shims (the feathers). After drilling holes along a line in the surface of the rock, you position the feathers in the holes (flat side in), then drive the plugs into the slot between them with a maul. The shims function as a guide that prevents the wedge from getting stuck. Eventually, a crack will appear.

rock bar: A steel bar with a beveled end, used as a fulcrum to move rocks. Rock bars are typically about 4 feet long, and weigh 16 to 18 pounds.

running (or unbroken) joint: A vertical seam that weakens dry-stone walls. When building rock structures, crew members always offset stones, using one rock to bridge two below it, so there is never a single unbroken line.

Above: A Yosemite trail crew at work in the wilderness. Photo: Steve Lynds. (All other photos courtesy of NPS.)