Many of Yosemite’s birds stay active all winter — and so do bird-watchers! The Conservancy’s resident naturalist, Pete Devine, shared some insights on the benefits of braving the cold weather to go birding during the quiet season.

Summer feels far away at this point. The days are short, trees are bare, and the ground is intermittently covered with snow. The busyness of the warmer months is distant, with far fewer visitors (and park employees) here for the quiet season.

Black-headed grosbeaks breed in Yosemite but winter in warmer territory. Photo: Marie Read

Wildlife dynamics shift, too. Ground squirrels and bears are sleeping, but deer tracks are everywhere. Some animals have left entirely. Many birds, such as grosbeaks, tanagers, swallows and (most) warblers, follow the food: Winter takes a toll on their bug-filled diet, so they fly south to Mexico or Central America.

When warmer weather returns, so will the migrant birds — with ample spring and summer insects, Yosemite is an ideal place for them to raise their families, and that’s worth the long flight from the tropics. (And they’ll be back just in time for Yosemite’s ornithology experts to continue the long-running songbird studies our donors support!)

Other birds stick around. They rely on their naturally water-resistant down “jackets” to stay warm and dry, and find ways to stay fed throughout the season.

Acorn woodpeckers can store thousands of acorns in a granary tree. Photo: Ann & Rob Simpson

I saw a few of those year-round residents during a recent walk in the Valley: Western bluebirds flew across Cook’s Meadow, a red-shouldered hawk hunted at Superintendent’s Bridge, and a kingfisher stole my gaze at Sentinel Bridge. Like dippers, these kingfishers can survive in frigid water, taking advantage of their specialized plumage to plunge in without a second thought.

Almost all of Yosemite’s woodpecker species live in the park year-round. Look for them on dry tree trunks, holding on with strong claws as they drill for insects under the bark, or snacking on acorns stashed in granaries.

Yosemite’s two chickadee species (mountain and chestnut-backed) are adept at finding seeds, berries and even frozen bugs year-round. Steller’s jays and ravens are similarly opportunistic and versatile feeders, finding food where they can and moving elsewhere if necessary.

Brown creepers are one of many birds studied through Yosemite’s songbird research program. Photo: Yosemite Conservancy

Brown creepers, which weigh only a few grams apiece, can make a hearty meal out of chilled spiders and insects they find behind flakes of bark; at night, up to a dozen of them huddle together for warmth. I got to see some of these tiny birds during my Valley walk the other day — they were part of a swarm that included kinglets, chickadees and yellow-rumped warblers, an example of the mixed-species flocks that many small songbirds form in the winter.

Beyond keeping my eyes and ears open during quiet strolls in the park, one of my winter birding highlights is the National Audubon Society’s annual Christmas Bird Count, an international citizen science project that has been going on for more than a century.

Since Yosemite joined the tradition in 1932, park participants have recorded more than 97,000 observations, contributing to an ever-growing data set that helps scientists study and protect diverse avian species. The Yosemite volunteers typically find 55-65 species — check out the park’s website to see what they’ve spotted in recent years.

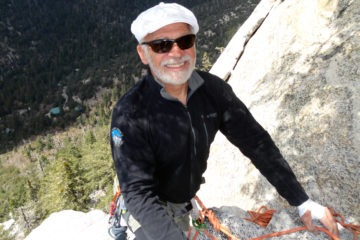

Pete Devine enjoys birding (and sharing his love for birds) in any season! Photo: Keith Walklet

Another winter highlight: Leading the Conservancy’s Outdoor Adventure focused on Yosemite’s remarkable assemblage of woodpeckers. There are a dozen woodpecker species here, more than anywhere else in North America! On this year’s outing, we saw six species, including a pileated woodpecker and a Williamson’s sapsucker.

There’s much to learn about these fascinating birds and the role they play in the Sierra ecosystem. For example, conifers killed by drought and beetle damage create new woodpecker foraging and nesting spots; in turn, woodpeckers create nest cavities used by a variety of mammals and birds, from martens and flying squirrels to kestrels, owls and even ducks.

There are clear pluses to paying attention to Yosemite’s off-season birds. Bare branches mean improved visibility. The hush that descends during this slower season makes it easier to hear chirps, taps and whistles. With the flashy flocks of neotropical migrant songbirds long gone on their journey south, you can focus on the robust year-round residents.

The best part? Shorter days mean you can sleep in a bit and still get out at dawn. Bundle up and give winter birds a look.