Robb Hirsch’s appreciation for the natural world is rooted in his neighborhood national park: Yosemite.

He grew up taking annual trips to the park, and followed his curiosity about nature to a career in field biology and on journeys around the world. Eventually, his interest in photography morphed from a convenient way to capture his work and travels into a profession.

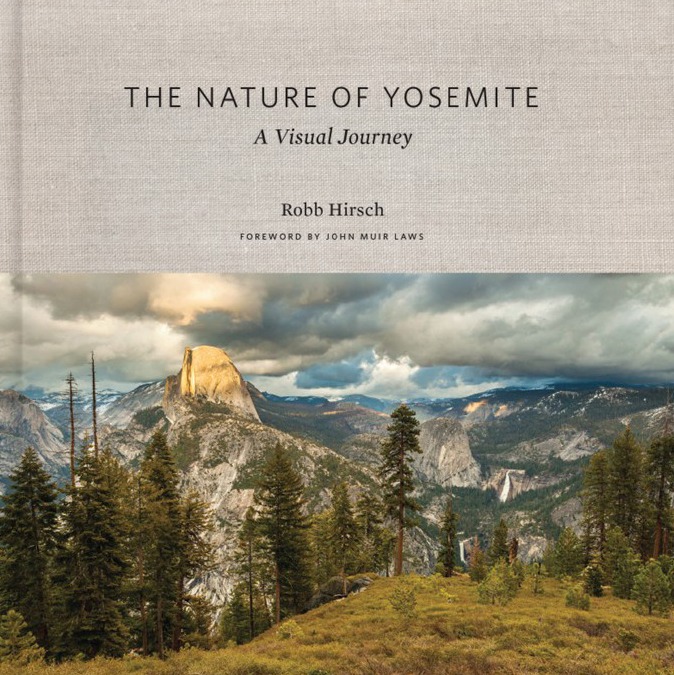

Robb’s photographic eye, biology background and infectious interest in the world around him coalesce in his first book: The Nature of Yosemite: A Visual Journey (published by Yosemite Conservancy). The 144-page book features Robb’s stunning images and insightful captions, as well as essays contributed by people with deep connections to — and knowledge of — Yosemite, including park scientists Greg and Sarah Stock (a geologist and biologist, respectively), our resident naturalist and longtime scholar of the Sierra, Pete Devine; and award-winning author Tim Palmer.

We checked in with Robb shortly after The Nature of Yosemite arrived on our bookstore shelves. Read on for Robb’s thoughts on the new book, his photographic process, and what draws him back to his “home mountain range” again and again — and enjoy a peek at some of the incredible images he shared during his recent takeover of our @yosemiteconservancy Instagram account!

1. We’ll start with a few superlatives. Tell us about…

- Your greatest challenge as a Yosemite photographer and naturalist.

In Yosemite, especially the Valley, there are so many incredible and well-known icons (El Capitan, Half Dome, all the waterfalls…), and they are all so photogenic that it can be difficult to exclude them from compositions. One of the greatest challenges, for me, as well as many other photographers in Yosemite, is focusing on the intimate landscapes, without any recognizable features, highlighting the subtle and lesser-known beauty of the park. Although it can be difficult to break away from the obvious photographic opportunities, I find huge gratification in these types of images.

- Your favorite season in the Sierra.

The short answer is whatever season I’m in the park. The longer answer is all the seasons are amazing and varied, from spring waterfalls, to summer flowers, to brilliant fall color. If I had to pick one, though, it would be winter. Under a fresh blanket of snow, Yosemite is one of the most magical places I’ve ever seen. The snow adds great contrast, helping to define the lines and shapes of the trees and granite. Counterintuitively, the extreme beauty can be nearly overwhelming photographically, making it difficult to tease out cohesive compositions with such stunning scenery everywhere. On top of the sheer beauty, the cold and challenging conditions keep many of the visitors at bay, adding to serene experience.

- Your top Yosemite spot to spend time if you have a spare day.

Wherever I am in the park! I don’t really have a favorite spot. What I most enjoy is exploring areas of Yosemite I haven’t previously visited, especially in the back country, searching for compelling scenes to photograph. I relish the hunt, seeing what’s over the next ridge, the view from on top of a peak or the scene on the opposite side of the meadow. The curiosity drives me to keep searching, and there’s nothing I’d rather spend time doing in Yosemite.

My photographic process isn’t necessarily dictated by my naturalist background. Rather, the naturalist in me is always guiding and helping make decisions to capture the best possible images. (More on that in a later question.)

My process typically consists of two different approaches. About half of the time I return to previously scouted locations, hoping to time the visit with something unique (stormy weather, peaking fall color, etc.). There are numerous locations with phenomenal photographic potential in my mental library — the key is being there during a special moment. The physical and intellectual challenge of finding compelling viewpoints, predicting when and under what circumstances the scene will be most photogenic, and getting out there when those conditions are present, is extremely rewarding and one of the most enjoyable aspects of photography for me.

Other times I head into the field without preconceived notions — encountering the unknown and unexpected fuels the excitement. In these instances, I strap on my photo pack with plenty of gear and head wherever the curiosity leads. I follow my intuition and what “feels” right in deciding the direction to go, using past experiences and my natural history knowledge as influences.

Whether I’m revisiting known spots or searching for new locations, adjusting and adapting as light and conditions change is a thrilling part of the experience and I relish the entire journey.

There are far too many places I want to explore and photograph to list here but there are certainly a handful of animals I haven’t seen but would love to. For all my time in the field as a biologist/photographer, I have never seen a mountain lion, though I can only imagine how many have seen me! A lion would be special to see anywhere, especially Yosemite.

There are a few rare or endangered species in the park I would love to lay eyes on, though I realize the odds are very slim — Sierra Nevada red fox, Pacific fisher and wolverine top that list. I’ve seen bighorn sheep from a distance in the park, but I’d love the opportunity to spend time with them to observe and photograph their interactions.

4. How does your background in biology play a role in your photography?

My biology/natural history background plays a critical role in my photography. This is most evident when shooting wildlife, as the training taught me skills to find critters and read their behavior. For instance, numerous times in the field, alarm calls of small mammals or birds have keyed me into the location of a coyote, pine marten, owl or other predator. By understanding the animals’ behaviors, I can usually minimize my presence, attempting to avoid affecting their actions. This is not only best for the well-being of the animals but also leads to more interesting images and a better overall experience.

The background has also taught me to be very observant in the natural world, so I tend to notice the little things like mosses and lichens. It forced me to be very patient, spending hours in blinds waiting for birds coming to and from nests, a critical asset in all types of nature photography.

Regarding landscape photography I think my background plays a more subtle role. Having spent so much time in the natural world, I’m very comfortable there, allowing me to tune into the surrounding scenery and identify the nuances and less obvious elements of a scene. Most of all I think there’s an overlap between biology, natural history and photography, with curiosity driving the passion to learn, see or capture something new.

5. What motivated you to publish The Nature of Yosemite, and what do you hope people take from the book?

Over the last decade or so, while I was building a portfolio of Yosemite images, I always had a book in the back of my mind as the long-term goal. I wasn’t certain of the format it would take but knew I wanted it to be more than a compilation of appealing photographs. I worked on getting a broad assemblage of Yosemite images, including grand landscapes and intimate photos, flora and fauna, frontcountry and backcountry, and scenes from all seasons, to reflect a good overview of the park.

The concept for the book came from giving a variety of natural history slideshow presentations. It was very clear to me that people were more inclined to stay engaged and retain the information presented when pretty pictures accompanied the talk. This was the root of the book’s approach — using photography as a vehicle to teach natural history and connect people to wilderness. The obvious impact and power that photography and other art forms wield was the driving force in wanting to get the imagery and message out there.

Most of all, I hope people take away a greater curiosity to explore and learn about the natural world. It would be wonderful if the book helped inspire people to get out in nature, whether in their backyards or Yosemite, and, as Jack Laws put it in the forward, “search for microbeauties.” This can lead to a greater understanding, appreciation and love for wilderness, which will hopefully result in us becoming better stewards of the land upon which we depend physically, mentally and spiritually.

There’s so much out here in the Sierra, both to learn ecologically and to explore physically, I feel like I’ve just barely touched the surface. The more I learn and understand, I realize how much more there is to know. Any window of time spent with amazing naturalists like Pete Devine, Dan Webster or Jack Laws is both inspirational and very humbling as their knowledge is so vast. From a natural history perspective, the sheer amount of interesting information and compelling anecdotes is limitless, at least for my lifetime.

Similarly, anytime I open a map of Yosemite, I’m struck by all the areas in the park I have yet to see, more so than what I have experienced. The park is huge, and with so many lakes, valleys, ridges and creeks to explore, it would take a lifetime to see it all — if that’s even possible.

The drive to explore new locations fuels my photography, and I have no shortage of interest or motivation to explore and learn about the Sierra. I’ve been to some amazing places around the world, but as much as I love traveling, I’m always happy and excited to return to my home mountain range.

Credit for all photos and captions in this post go to Robb Hirsch … including, of course, the sumptuous shot of the frozen Tuolumne River at the top of this post. Here’s how he describes that scene:

The winter of 2011–12 was truly a special one. Visitors to Yosemite were presented with a rare opportunity to drive into the high country during a time of year when access is usually limited to skis and snowshoes. Typically, Tioga Road is closed after the first big snow in the fall and stays closed until the following spring or summer. That winter, however, was one of the driest on record, and the road was open through mid-January, providing a unique window of access.

I spent several frigid days wandering around Tuolumne Meadows, pondering life at 8,600 feet, where the nightly temperatures drop to single digits and daytime temps hover just above freezing. It was so cold, I wondered about the animals. Most birds had moved on, but small mammals, amphibians, and fish were still nearby, utilizing a variety of specialized adaptations to survive until the spring thaw.

Photographically, I gravitated to the alluring ice formations along the Tuolumne River, working to capture them as unique entities on their own and in the context of the surrounding landscape.

Our sincere thanks go out to Robb for taking the time to share his insights and images with us — and with you! To see more of Robb’s work, head to our online bookstore to purchase your copy of The Nature of Yosemite, follow @robbhirschphoto on Instagram and visit robbhirschphoto.com.