These days, we take GPS (global positioning system) for granted. It’s in our phones, in our cars, in our computers — and many of us rely on it for day-to-day navigation, sharing our travels, and more. But the technology has a different use within Yosemite; it is invaluable for scientists studying wildlife in the park. From bears to birds to bighorn sheep, GPS is a critical tool for researchers and their work to study and protect both ubiquitous and rare species.

Bears

A tagged black bear rests in the Valley. Conservancy donors have contributed nearly $279,000 to bear-specific GPS projects in the past decade, and more than $2M to other bear-related projects. Your support is working to protect this iconic Yosemite species. © Bob Roney

Since the 1990s, wildlife biologists have used radio telemetry to monitor black bears’ activities in Yosemite. This precursor to GPS technology allowed resource managers to find collared bears of interest via a radio signal — but it only worked within a small range of about a mile or two.

Now, real-time GPS tracking allows researchers to continually and consistently observe bear movement across the park, identifying patterns that allow responsive management decisions, such as temporary speed restrictions on Tioga Road when bears are actively foraging nearby.

Longer term, this wealth of data offers ample research potential into bear habitat, food sources and availability, movement patterns, and more.

There is a common misconception that tagged and collared bears in the park are “in trouble,” or that those tags and collars amount to unnecessary human interference. Actually, it’s humans who are encroaching on black bear habitat. And the tags and collars— which are harmless to the bears — help keep them safe. “While they might not look natural, the goal [of the GPS collars] is to encourage bears to remain wild by staying away from humans,” says Caitlin Lee-Roney of Yosemite’s Human–Bear Management Program. The simple presence of people often tempts bears to forgo their instinctual food sources, such as acorns, in favor of the calorie rich food humans bring and eat daily at the campgrounds and picnic tables. Lee-Roney knows exactly how dangerous a single incident of a bear successfully finding human food can be. She and her team rely on donor-supported GPS tracking technology to help prevent those incidents, allowing bears to coexist with humans in healthy and sustainable ways.

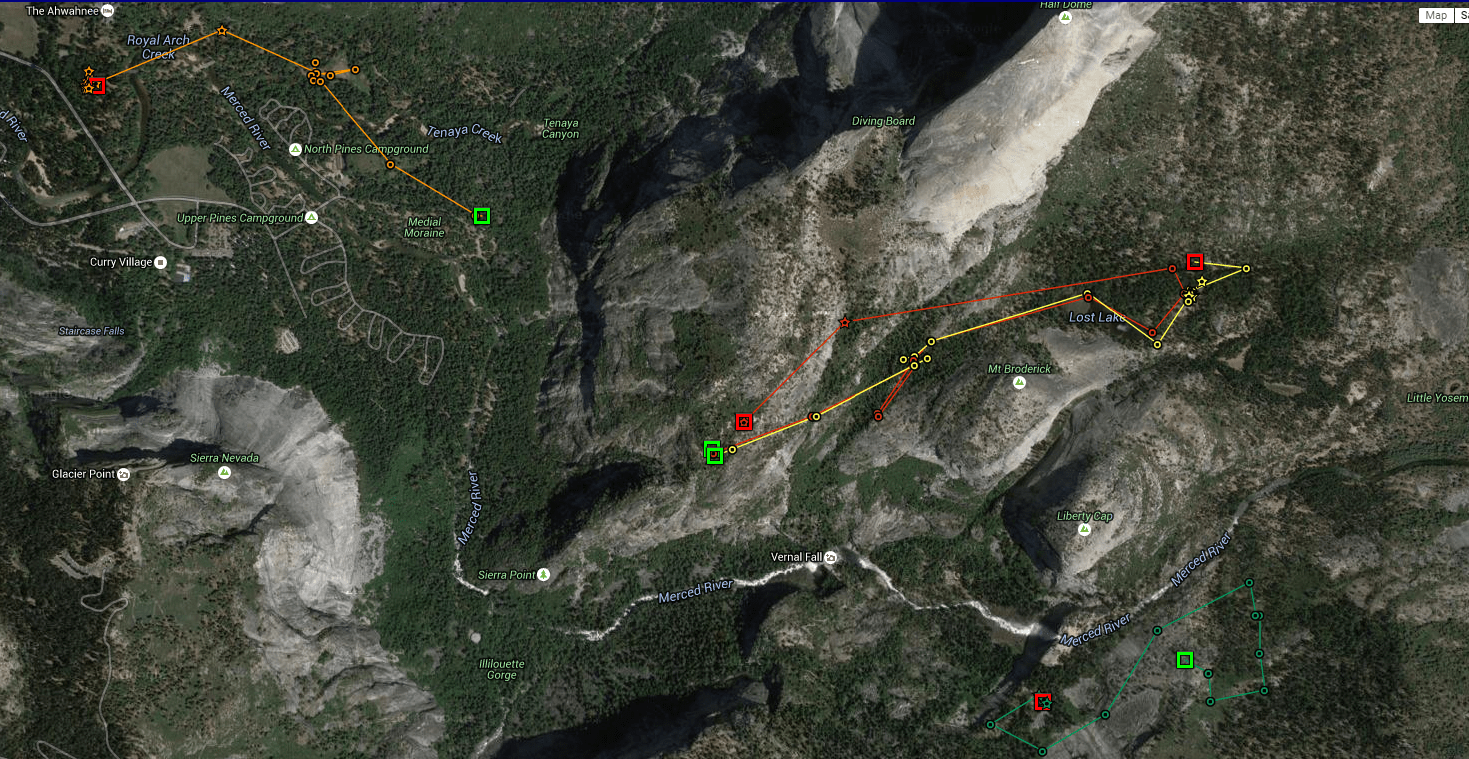

A GPS tracking map that shows the behaviors and habits of wild bears. This bear map is one of many resources that can be found at keepbearswild.org, a project made possible by donor support. © NPS

“We want to shift bears back to their natural behaviors: avoiding people and eating natural foods,” Lee-Roney says. And it’s working. The combination of monitoring devices and bear-proof food storage has led to a massive reduction in annual bear related incidents in the park — from a high of 1,584 in 1998 to just 55 in 2021. Lee-Roney and her team only target and tag or collar bears after visually observing that they are interacting with developed areas, which amounts to fewer than 25 of the 300 to 500 bears in Yosemite. Despite the advanced technology that helps track habituated bears (those that have become desensitized to the presence of humans) in Yosemite Valley, the actual method of deterring the bear is as analog as ever. When rangers receive an alert that a collared bear is in or approaching a campground or parking lot, they grab their equipment and get ready to yell.

“We do whatever we can to convince them that being around humans is a bad idea,” Lee-Roney says. In this way, GPS tracking and in-person ranger interventions protects both wildlife and people.

Bighorn sheep

Bighorn sheep are tracked using GPS collars, which helps researchers monitor the species’ recovery in the park. © Steve Yeager

Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep are a unique, genetically distinct subspecies of bighorns, and they only live in their namesake mountain range. After decades on the edge of extinction, they are slowly reclaiming a foothold in their Yosemite high country habitat. Conservancy donors have played an invaluable role in that recovery since the species’ initial reintroductions in 1986 and 1988, as has GPS tracking.

When Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep were listed as endangered in 2007, GPS tracking was identified in the recovery plan as an important tool for monitoring the population. With help from Conservancy donors in 2011, 30 individuals were fitted with collars. Prior to the 20th century, Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep populations likely numbered in the thousands. But the arrival of Western settlers brought unregulated hunting and exposure to foreign diseases carried by domesticated sheep.

Today, GPS data helps resource managers and researchers from the National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, and California Department of Fish and Wildlife to monitor bighorns’ survival, habitat use, and movements — and to intervene, when necessary, to ensure they avoid contact with domestic sheep. Domestic sheep are still grazed near park boundaries on Forest Service land, and they could potentially hinder bighorn recovery efforts without effective monitoring.

Modern GPS technology is also helping biologists learn how the species is faring is a changing climate. As the Sierra Nevada experiences climate whiplash — extremely wet winters juxtaposed with extremely dry winters — researchers are studying the bighorns’ GPS tracks to understand how they navigate these new climate challenges.

Owls

Previous issues of this magazine have highlighted our donor-supported effort to restore Ackerson Meadow to its natural hydrology and reinstate its former glory as a mid-elevation habitat haven. This year and next, GPS tracking of Yosemite’s great gray owls will reveal where the species are foraging, roosting, and nesting. Biologists will use this information to help inform active restoration activities that further optimize the habitat characteristics on which the owls rely. With your support, in 2022, wildlife biologists will tag up to seven individual great gray owls with GPS tracking devices, which will record their locations at regular intervals and help map their travel patterns. Biologists can use this location data in conjunction with noninvasive methods, including lidar data, DNA analysis, and field observations, to monitor their movements and document favorable conditions at the owls’ nesting and hunting sites

“Combining technology allows us to zoom in and zoom out at all spatial scales with precision to examine how animals are interacting with the landscape,” says Sarah Stock, a wildlife ecologist in Yosemite. Stock and her team hope to make roadsides less attractive to these rare and threatened owls, which are regularly lost to vehicle collisions, and to create the ideal water levels and vegetation structures for them to forage in Ackerson and other nearby meadows. If resource managers can replicate the owls’ preferred conditions during rehabilitation, they’ll make serious strides toward ensuring the species’ survival. This project is made possible by donor support and through collaboration with the Institute for Bird Populations, which relied on similar tracking technology to study raptors in the northern Sierra Nevada in recent years, and which has contributed to several successful Conservancy-funded bird projects.

Pacific fishers

The rare Pacific fisher is tracked using GPS and its habitat is assessed using lidar. © U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Southwest Region.

The Pacific fisher — a relative of the mink and the otter — is a medium-size, forest-dwelling mammal. The isolated population of fishers in the southern Sierra Nevada, which scientists estimate at fewer than 300 adults, faces rapid habitat loss driven by wildfire, tree mortality, and climate change. The species was designated as federally endangered in May 2020. There’s reason for hope, however.

With your support, park biologists have been surveying and monitoring fishers with advanced tracking technology since October 2021 with great success. Using a combination of advanced GPS collars and conventional telemetry methods, Stock and her team have captured and collared 10 male and five female fishers. Their goal is to determine fisher travel paths in and around recent wildfire footprints, but their tracking efforts have already revealed fishers in unexpected places, including Yosemite Valley!

In late March, when the fisher breeding season began, the project team transitioned to tracking pregnant females to identify the den trees where they will have their young offspring.

“This is an exciting time to discover a new generation of fishers in the park,” Stock says. “We hope our results will tell us more about the number of fishers living here and, more importantly, the habitat they need to survive in a constantly changing landscape.” While tracking collars for smaller animals, such as fishers, are not as versatile as larger models (such as for bears and sheep), and have limited battery life, they can still provide critical, detailed data on habitat use and suitability, as well as inform successful management strategies that balance the species’ immediate and prolonged needs. If biologists such as Stock can identify where a female fisher has chosen to den, for example, that area can be temporarily protected from interference while fire crews perform prescribed burning elsewhere, hopefully preventing high-severity fire and protecting fisher habitat into the future. In this way, technological advances in GPS monitoring — and the generosity of you and other donors who make such tools accessible to Stock and her colleagues — are helping protect the Pacific fisher population from near extinction.

This was written by Elizabeth Sherer for the Spring/Summer Yosemite Conservancy Magazine (published in May 2022). Click here to read the magazine in full.