Above: A 2015 Yosemite Climber Steward answers climbing questions. Photo: Courtesy of NPS.

Towering more than 3,000 feet above the floor of Yosemite Valley, El Capitan draws rock-climbers from around the world. In 1958, Warren Harding, Wayne Merry and George Whitmore completed the first ascent of this massive glacier-carved granite cliff; today, dozens of routes snake up El Capitan’s two faces and prominent “Nose.”

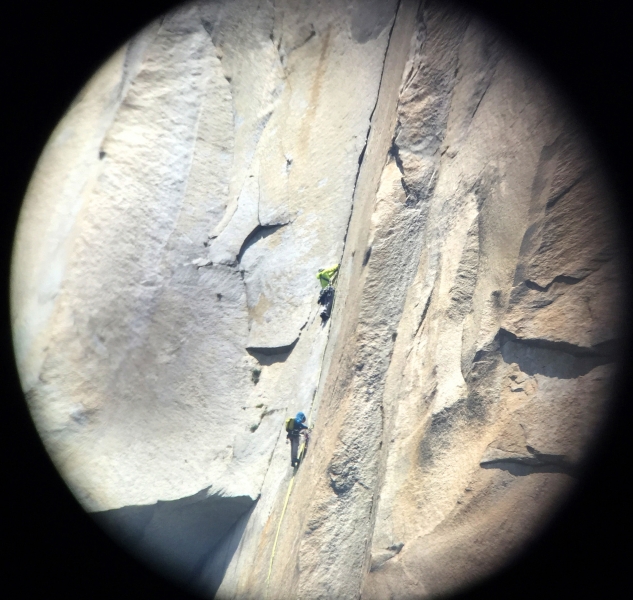

Curious about how — and why — people climb this storied Sierra monolith? Climbing rangers and Climber Steward interns fun “Ask a Climber,” a seasonal interpretive program our donors support in the park. Between May and October, you’ll find them in El Capitan Meadow with telescopes, climbing gear and answers to your questions about Yosemite’s vertical environment.

We put together a list of Yosemite climbing FAQs that rangers and Climber Stewards often hear at the bridge. Have a question not listed here? Share it with us on social media (we’re @yosemiteconservancy on Facebook and Instagram, and @yoseconservancy on Twitter), or head to the Ask a Climber station in the park!

Top Nine “Ask a Climber” Questions

9. How many days do climbers spend on El Capitan?

Typical teams climb popular routes, such as the Nose, the Salathé and the Zodiac, in 3-5 days. More difficult climbs, such as the Sea of Dreams and the Pacific Ocean Wall, demand extra time. Spending multiple days on a rock wall requires quite a bit of gear (see below), but some fit and experienced teams will leave their “haul bags” behind to tackle the “Nose in a Day” (NIAD) challenge, using speed-climbing techniques to work their way up El Capitan’s jutting prow. Some NIAD climbs take a full 24 hours; the record, set by Jim Reynolds and Brad Gobright in October 2017, is 2 hours, 19 minutes, 44 seconds. (On a historical note, Harding, Merry and Whitmore took 47 days, spread out over 16 months, to create a route and complete the first ascent of the Nose in 1958.)

8. What equipment do climbers carry?

Big wall climbers carry two ropes, a pulley, 30-50 carabiners, slings (loops of rope or tape) and other hardware, as well as protective equipment such as spring-loaded camming devices, metal stoppers, hooks, and pitons (metal spikes driven into cracks in the wall to serve as anchors). That might sound like a lot, but it all comes in handy!

When leading a pitch (a ~100-foot section of rock), climbers carry two ropes: one tied around the waist, to catch them if they fall, and a second called the “haul line.” When they finish a pitch, lead climbers secure themselves to the wall, and then use the haul line and a pulley to hoist up the “haul bag,” which holds food, water, clothes, sleeping bags and other gear. Depending on the climb, haul bags can weigh as much as 50 or 100 pounds!

7. How do climbers get down after they reach the top of El Capitan?

Most teams will head to the East Ledges descent, a sloping ramp visible from the Valley floor. The descent down the ramp, which requires hiking, “down-climbing” and rappelling, is a tricky off-trail route that should only be attempted by expert climbers. Other descent options include hiking down the steep Yosemite Falls Trail or taking the longer, flatter journey west to Tamarack Flat.

6. How do climbers go to the bathroom while they’re on the wall?

To answer the call of nature when they’re hundreds or thousands of feet above the Valley floor, climbers use double-sealed bags, sold under a variety of names but often referred to as “wag-bags”, which offer a sanitary way to store, transport and dispose of solid and liquid waste. During a climb, wag-bags are stored in a small, separate bag that is used exclusively for waste disposal. This system isn’t climbing-specific — wag-bags can be used in other outdoor recreation activities, such as backpacking. (For more tips on ways to “leave no trace” when you’re exploring the outdoors, read our LNT blog post.)

5. What’s the hardest climb on El Capitan?

Short answer: They’re all really difficult!

Longer answer: Because there are many styles of climbing, there are many ways to answer this question. In “aid climbing,” climbers use gear to stay attached to the wall and pull themselves upward. On tricky pitches, like those on the Reticent Wall and Surgeon General (both on El Capitan’s southeast side), it can be tough to place pieces of aid equipment securely or close together.

In “free climbing,” climbers use gear to help prevent falls, but rely only on the wall’s natural features to ascend. The Valley offers plenty of difficult pitches for climbers to practice their free-climbing skills before taking on El Capitan routes such as the Freerider (on the southwest face), where they navigate pitch after pitch of difficult unaided climbing thousands of feet above the Valley.

The Dawn Wall (which catches the morning light on El Capitan’s southeast face) is often considered the most difficult climb not only in Yosemite, but in the world. In January 2015, Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson made headlines for completing the first free ascent of that route, working together for 19 days together on the wall to reach the summit.

4. How do big wall climbers sleep?

They lie down and close their eyes just like everyone else! The big difference? When climbers zip up their sleeping bags, they are wearing harnesses and are attached to the wall with a rope and anchor. Sometimes, climbers put their sleeping bags on flat stretches on the wall. El Capitan might look smooth from a distance, but if you zoom in, you’ll see numerous towers and ledges — see if you can spot some of those natural resting spots through the Ask a Climber telescopes. When natural ledges aren’t an option, climbers sleep on a “portaledge” (short for “portable ledge”), a collapsible metal cot that attaches to an anchor.

3. What happens if climbers fall?

Climbers constantly monitor and evaluate the potential for a fall. Lead climbers pay attention to how far away their closest piece of protective gear is, to ledges below that they might hit before their rope stops a fall, and to how far they have to go before they can rest or place another piece of equipment.

Quick physics: Imagine the fall as a pendulum. The rope is the arm, and the last piece of protection is the pivot point. When a fall occurs, the climber is the mass at the end of the arm that has just been dropped from directly above the pivot point. Climbers who fall when they are 5 feet above their last piece of protection will drop twice that distance (10 feet), because the rope will tauten only after they are 5 feet below that protection.

The rope is built to absorb the force of the fall. Usually, the climber comes to rest with a quickened pulse but is usually unharmed. A good, clean fall can even help reduce anxiety, allowing climbers to shake off their nerves and continue pushing toward the summit.

2. What happens if climbers get injured?

Most of the time, teams complete climbs with few or no incidents. In cases of minor injuries, they either continue to the summit or perform a self-rescue by rappelling to the ground.

If self-rescue is not an option, climbers contact the Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR) team, a group of highly skilled National Park Service staff and volunteers. From conducting complex helicopter-based maneuvers to using long ropes to lower rescuers to injured climbers, the YOSAR team employs a range of “high-angle” techniques designed for very steep terrain – including many that have been pioneered and refined in Yosemite.

In spring, summer and fall, you’ll find YOSAR volunteers, known as “SAR-siters,” living in Camp 4, the first-come, first-served campground near Yosemite Falls, where they can be ready for action when an emergency arises. Our donors have funded a series of grants to replace aging tent cabins that house the SAR-siters, to ensure that these talented volunteers have a comfortable place to call home during their time in the Valley.

1. How do climbers know where to go?

Back in the mid-1900s, the climbers establishing the first routes on El Capitan weren’t sure if it would be possible to scale the entire face. Through trial and error they developed the routes, skills, hardware and partnerships necessary to ascend Yosemite’s grand granite walls.

Today, climbers draw on an array of print and digital guidebooks, which offer a wealth of useful information, including detailed maps, pitch descriptions, and notes on gear needed for different routes. Even with maps and notes, climbers still have to translate paper to granite, “reading” rock to figure out where the guide is telling them to go. This spring, as they hone their skills and puzzle through challenging pitches, modern big wall climbers will tap into the creativity, resilience and problem-solving skills exemplified their pioneering predecessors as they continue to strive for the summit of Yosemite’s world-famous walls.

You don’t have to rope up and carry carabiners to play a part in the Yosemite climbing world! In addition to supporting Ask a Climber, our donors fund grants to improve access trails for popular climbing routes and empower teens to explore nature through climbing and other activities. Learn more about how your gifts can make a difference in Yosemite, and be sure to stop by the Ask a Climber station (May 15-Oct. 15) if you’re planning a trip to the park!