Alternate Histories

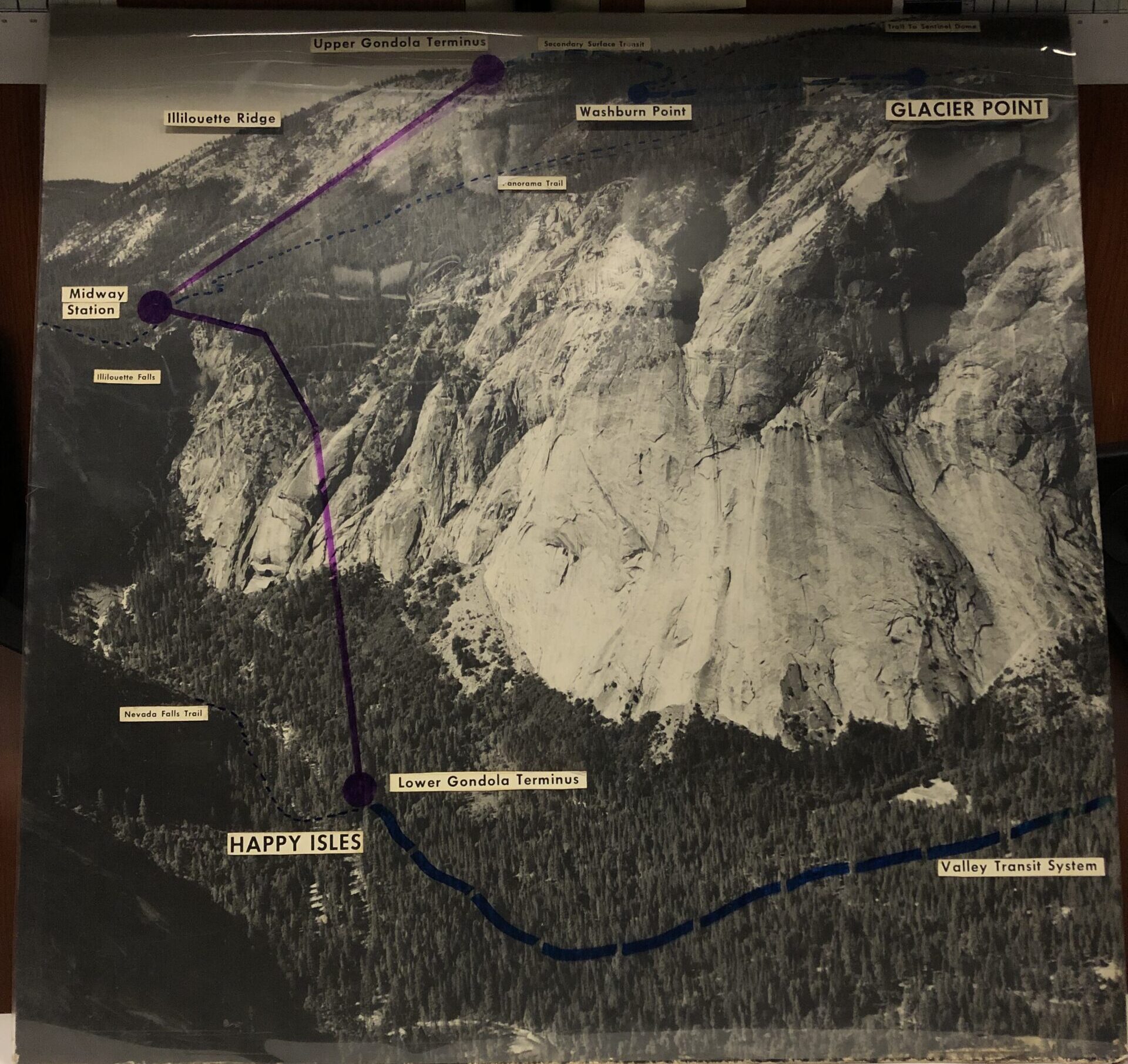

Picture the scene: You’re standing at Happy Isles, looking up through the trees, thinking about Glacier Point. You want to see the view from the top, so you hop into a gondola that glides up over the Nevada Fall trail, pausing at a midway point of Illilouette Ridge before gently coming to a stop near Glacier Point.

For many, the thought of a gondola to Glacier Point is unthinkable. Infrastructure of that scale would dramatically alter the scenic landscape and wild beauty of Yosemite. But it’s one of the projects that could have happened in the park. As we celebrate Yosemite Conservancy’s centennial, we thought you might like to learn about some ideas from the past that would have radically altered the Yosemite we know and love today.

Glacier Point cable car

The Glacier Point cable car was proposed in 1929 by Donald Tresidder, the park’s concessionaire, as an alternative means of transit from the Valley to Glacier Point. An Austrian engineer from the Adolph Bleichart Company visited the park to investigate and plan a route for the cableway, and to scout for a second route that would transport visitors from the Tenaya Creek Canyon up to Tenaya Lake. The project was deemed to have some merit by the Yosemite National Park Board of Expert Advisors, who believed it could alleviate congestion on park roads. Ultimately, however, it was decided that the high visibility of the cable system would have a serious impact on the natural beauty of the Valley landscape, and the board expressed concerns that visitors would regard the cable car as an attraction rather than a means of transit.

The proposed route of the Glacier Point gondola, which would have left from Happy Isles to a midway station at Illilouette Falls and ended at the Glacier Point Hotel. Image: Yosemite Archives

Car-free Yosemite

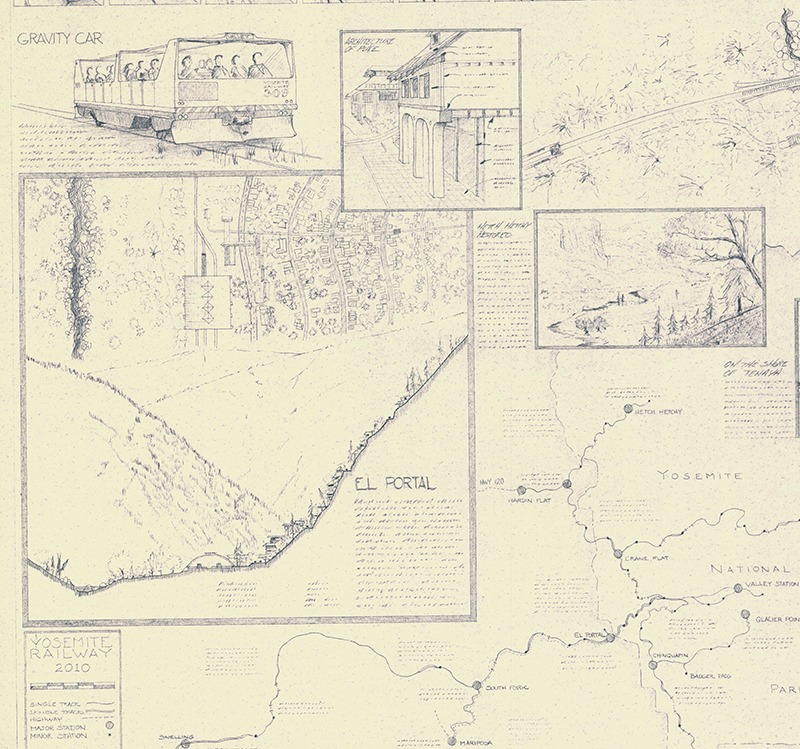

Thirty years ago, a plan was drawn up to envision a car-free Yosemite by 2010, which proposed to use the former postal railway line to El Portal and develop multiple tracks out into the Valley from there. It said: “Yosemite is being destroyed by the technology we use to visit the place. This plan is threefold. First, the development of a railroad to replace all highways in the park; second, the creation of a new town in El Portal, allowing removal of all buildings in Yosemite Valley; and third, a program to restore portions of the park damaged by roads, buildings, and campsites.” The project was slated to cost $3 billion and aimed to be 100% solar powered, but never reached a stage where it was considered.

Planning drawings for a gravity car monorail in Yosemite Valley

Winter Olympics

These weren’t the only plans that got shelved. In Yosemite’s early days as a national park, winter access was a challenge. The completion of Tioga Road in 1915 opened the park to year-round visitors, and after a trip to Switzerland to see the 1928 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, Donald Tresidder returned to Yosemite with a deep enthusiasm for cultivating the park as a winter sports destination.

Tresidder was so committed to the idea that he proposed a bid to host the next Winter Olympics in Yosemite! The necessary facilities accelerated the survey and development of the winter sports park, leading to the identification of Badger Pass as a fine ski area. The competition was so fierce that the head of the Lake Placid, N.Y., bid wrote to Tresidder to ask him to withdraw. Lake Placid won out, despite experiencing one of its warmest winters on record. The ice-skating tryouts were held in Yosemite, which holds the accolade for being the only national park ever to have proposed an Olympic bid.

Skiers at Badger Pass in 1937

Yosemite Zoo

Yosemite Valley briefly housed a zoo behind Yosemite Village. Contentious from the get-go, the zoo held mountain lions, a bear, and deer, all kept in enclosures. The zoo began in 1918, when a mountain lioness was killed by a ranger and her cubs were “rescued” to be hand-reared in the Valley. Due to the human intervention in their development, the lions were regarded as tame, and children and adults were sometimes allowed to enter their enclosure to feed them. Both park officials and scientists were uncomfortable with the zoo, but it remained open until 1932. National parks were still in their infancy, and proper stewardship and land management had not been approached with the same care and conservation we now expect from the National Park Service.

Park management has carefully considered hundreds, if not thousands, of proposals during the past 100 years and more. As we celebrate our centennial and the success of the unique partnership Yosemite Conservancy shares with Yosemite National Park, we are excited to think about the sorts of grants and projects that will protect Yosemite for generations to come.

Yosemite Zoo. Image: NPS

With thanks to both the Research Library and the Yosemite Archives. This story featured in our Spring/Summer Yosemite Conservancy Magazine, and was written by Megan Orpwood-Russell.